Fan-Out in Social Media Feeds Explained from First Principles

Source: Dev.to

A First‑Principles Walkthrough for Software Engineers

If you’ve ever opened a social‑media app and scrolled through a feed, you’ve interacted with one of the most aggressively optimized systems in modern software. It looks harmless—a list of posts ordered by time or relevance. Nothing fancy.

Under the hood, it’s a small war against latency, scale, skew, and human behavior.

This post is about fan‑out, one of the core ideas behind how social‑media feeds are built. We’ll approach it from first principles, assuming you’re a software engineer but not assuming you’ve designed systems for millions or billions of users. No buzzwords first. No architecture flexing. Just careful reasoning.

Start with the simplest possible question

Before talking about fan‑out, we need to agree on what problem we’re actually solving.

A social‑media feed, stripped of branding and algorithms, boils down to this:

When someone creates a post, other people should be able to see it.

That’s the entire feature. Everything else—likes, ranking, recommendations, notifications—exists because that simple requirement becomes brutally expensive at scale.

Now translate that sentence into system language:

A single write operation must result in many read‑visible outcomes.

That transformation from one write to many reads is what we call fan‑out. Fan‑out is not a feature; it’s a consequence.

First principles: what reality forces on us

Before choosing designs, we need to understand the shape of the problem space. These are not opinions; they are constraints imposed by how people and computers behave.

Reads massively outnumber writes

In any social system, users read far more than they write. One post might be read thousands, millions, or even hundreds of millions of times, but it is written exactly once.

This asymmetry matters. Any design that makes reads expensive will suffer constantly. Any design that makes writes expensive suffers only occasionally. At scale, systems almost always choose to hurt occasionally rather than constantly.

Social graphs are uneven in a violent way

Most users have a small number of followers. A few have an enormous number. There is no smooth curve here; it’s a cliff.

This means the cost of “show this post to followers” is usually small, but sometimes astronomically large. If your design does not explicitly account for that, it will work beautifully in tests and collapse in production.

Latency is a user emotion, not a metric

From a human perspective, the difference between 100 ms and 300 ms feels negligible. The difference between 300 ms and 1 s feels broken.

Feeds must feel instant. That means feed reads must be fast not on average, but almost always. Tail latency matters more than mean latency.

Storage is cheaper than computation and network hops

Disks are cheap. CPU time and network calls are not. Every additional query, every additional service hop, every additional merge step shows up as latency.

This pushes real systems toward pre‑computation and caching, even if that means duplicating data.

Hold onto these constraints. Fan‑out exists because of them.

The most obvious solution (and why it fails)

The simplest way to build a feed is to compute it when someone asks for it. This approach is usually called fan‑out on read.

How it works conceptually

- When a user opens their feed, the system looks up who they follow.

- It fetches recent posts from each of those users.

- It merges all those posts together, sorts them, ranks them, and returns the result.

Nothing is pre‑computed; everything happens on demand.

Why everyone starts here

- It feels clean.

- It avoids duplication.

- Writes are trivial.

- Storage usage is low.

- The logic maps directly to the product definition: “show me posts from people I follow.”

If you’re building a prototype or an early‑stage product, this often works fine—hence its temptation.

Why it collapses at scale

- The cost of reading a feed becomes proportional to the number of people you follow, so a single request may fan out into dozens or hundreds of database queries.

- Cache misses amplify the problem.

- Ranking logic adds computation.

- Network latency stacks up.

The result is unpredictable latency: some feed requests are fast, others are painfully slow. Once real traffic arrives, the system starts thrashing.

This violates a fundamental rule of scalable systems: read paths must have bounded cost. Fan‑out on read makes reads expensive at the exact moment users care most about performance.

Turning the problem inside out

To fix this, engineers flip the problem. Instead of computing feeds when users read, they compute feeds when users write. This approach is called fan‑out on write.

How it works

When a user creates a post, the system looks up their followers and inserts a reference to that post into each follower’s feed ahead of time. When a follower later opens their feed, the system simply reads from a pre‑built list.

Why this works so well

- Feed reads become simple lookups—no merging, no heavy computation.

- Latency becomes predictable and low.

- It aligns perfectly with the earlier constraint that reads dominate writes: you pay a cost once and benefit many times.

If all users had similar follower counts, this would be the end of the story. Unfortunately, humans ruin everything.

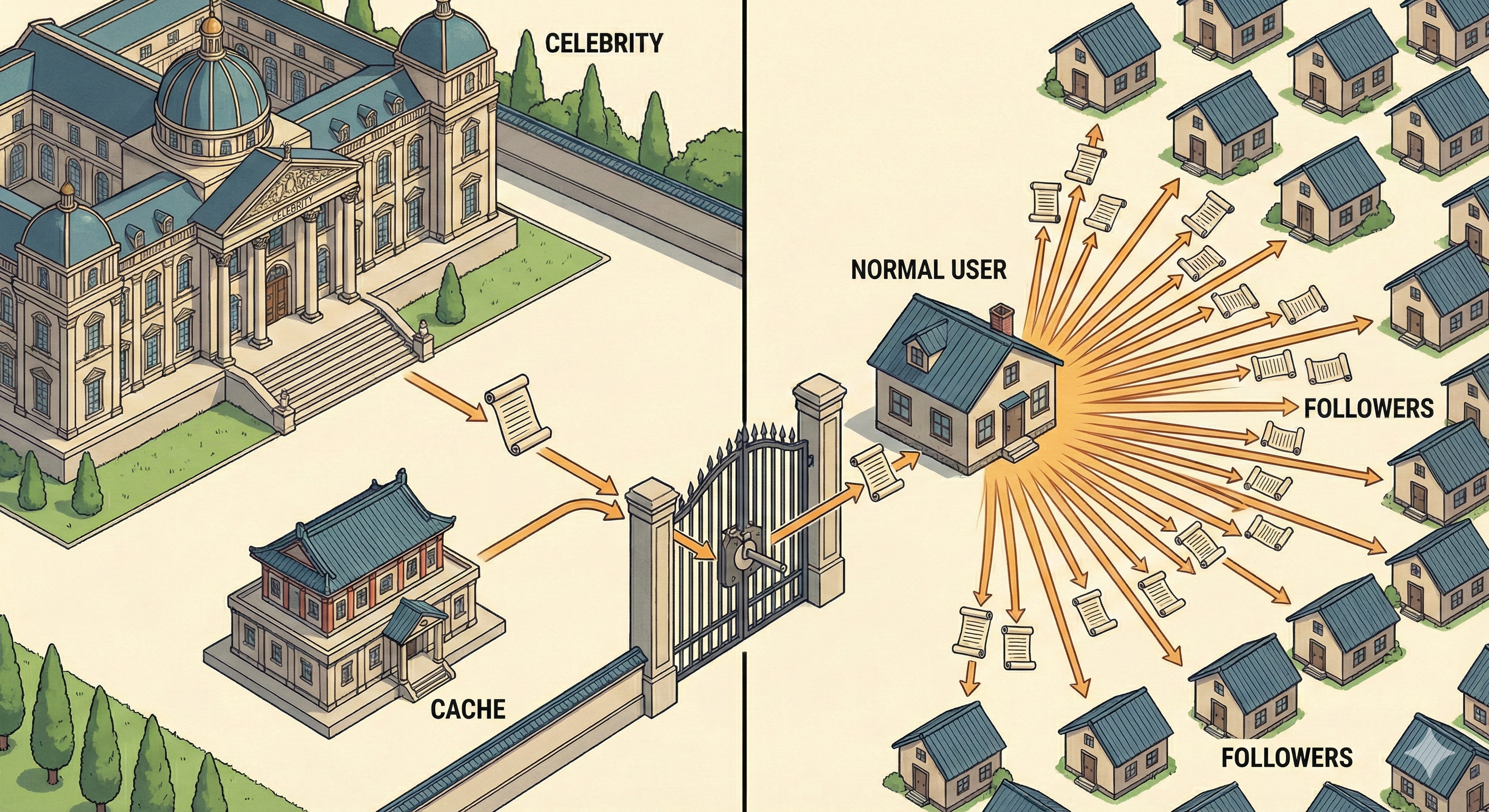

The celebrity problem

Fan‑out on write has a hidden assumption: that the number of followers per user is modest. When a user with millions of followers posts, the system must write millions of entries in a single transaction, which can overwhelm storage, CPU, and network resources.

The rest of the article (not shown) explores strategies for handling this “celebrity” edge case, such as hybrid fan‑out, lazy propagation, and sharding techniques.

End of cleaned markdown segment.

The Cost of Fan‑out on Write

For most users, fan‑out on write is manageable.

If someone has 200 followers, inserting 200 feed entries isn’t a big deal.

But some users have millions of followers.

For them, a single post triggers millions of writes—possibly across shards, replicated, and queued. Even asynchronously, this creates massive pressure on the system.

Rule: No single request should have unbounded cost.

So pure fan‑out on write fails, just in a different way.

The Solution Real Systems Converge On

Large social systems don’t pick one approach; they combine them.

This is called a hybrid fan‑out model.

How It Works

| User type | Fan‑out strategy |

|---|---|

| Manageable follower count | Write‑time fan‑out – posts are pushed directly into follower feeds. |

| Extremely large follower count | Read‑time fan‑out – posts are pulled into feeds when a user reads. |

This caps the worst‑case write cost while preserving fast reads for the majority of users.

- Is it elegant? Not really.

- Does it survive real traffic? Yes.

That trade‑off is what matters.

Rethinking What a Feed Actually Is

A common misconception: a feed is not a query.

A feed is a materialized view – a pre‑computed, per‑user index of content references (pointers), not the content itself.

Typical feed entry fields:

user_idpost_idtimestampmetadata(used for ranking)

The post content lives elsewhere.

This separation lets systems:

- Rebuild feeds

- Re‑rank content

- Handle deletions without rewriting everything

Seeing feeds as cached indexes turns fan‑out into a maintenance problem, not a computation problem.

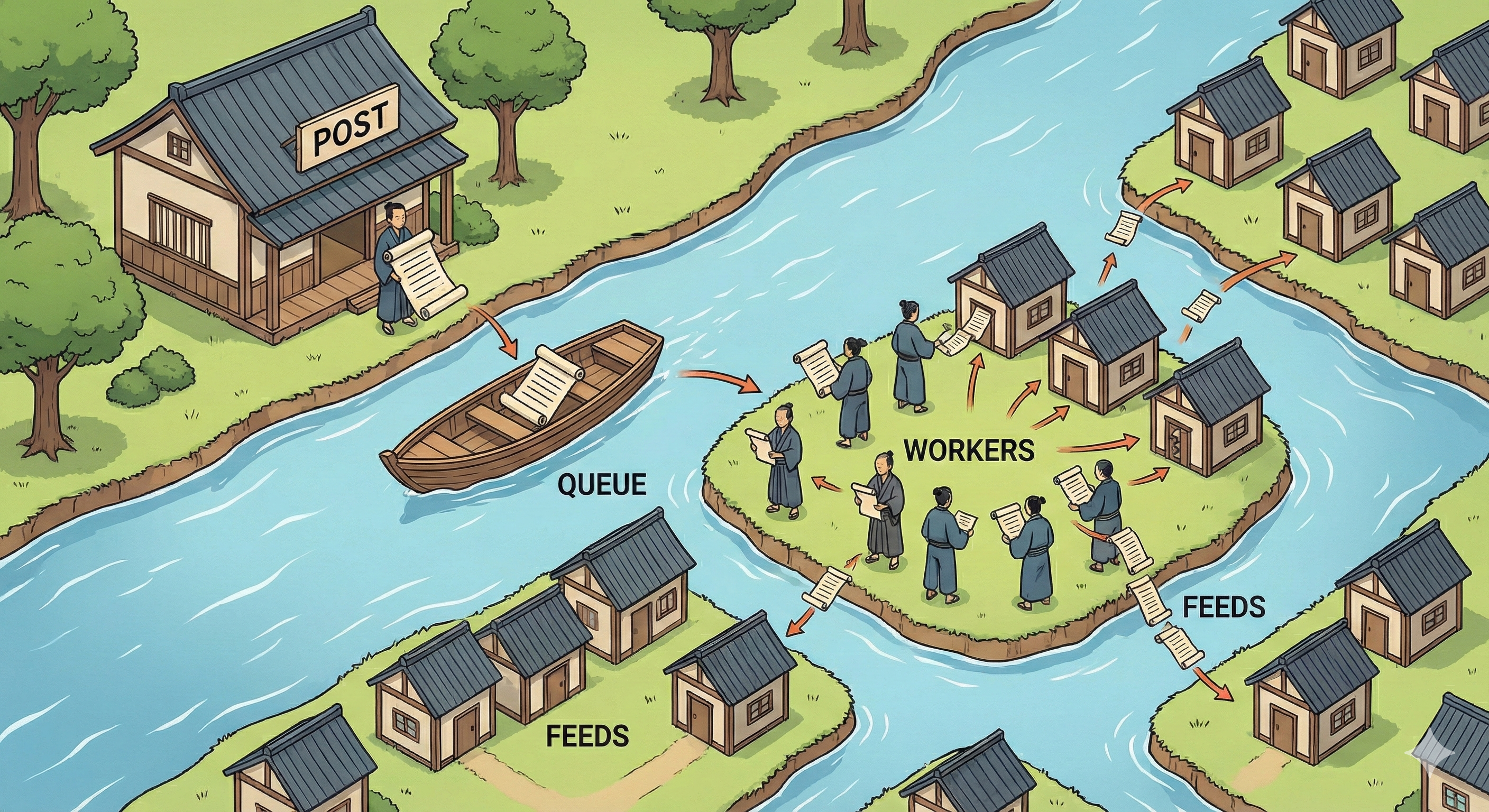

Event‑Driven Fan‑out Is Mandatory

Never perform fan‑out synchronously.

- Emit an event when a post is created.

- Background workers consume the event and update feeds asynchronously.

Benefits:

- Retries and back‑pressure handling

- Recovery from failures

- Alignment with the reality that social media is eventually consistent

Users can’t tell whether a post appeared in their feed after 200 ms or after one second. Your infrastructure definitely can.

The Mindset That Actually Matters

When designing a feed system, the specific database or queue technology matters less than the questions you ask:

- What is the worst‑case fan‑out size?

- Is the cost of a request bounded?

- What happens when workers lag?

- Can feeds be rebuilt?

- How do deletions and privacy changes propagate?

Fan‑out isn’t about cleverness; it’s about respecting constraints.

A Final Analogy That Actually Holds

- Fan‑out on read = cooking every time you’re hungry.

- Fan‑out on write = meal prep.

Cooking sounds flexible until you have to serve millions at once.

At scale, preparation wins.

The Takeaway

Fan‑out is not an optimization; it’s the unavoidable result of turning one action into many experiences under extreme skew.

Once you understand that feeds are pre‑computed, per‑user views maintained under constant pressure, the rest of social‑media system design starts to make uncomfortable sense.

And yes, it only gets harder from here.