How to structure technical planning for engineering

Source: Dev.to

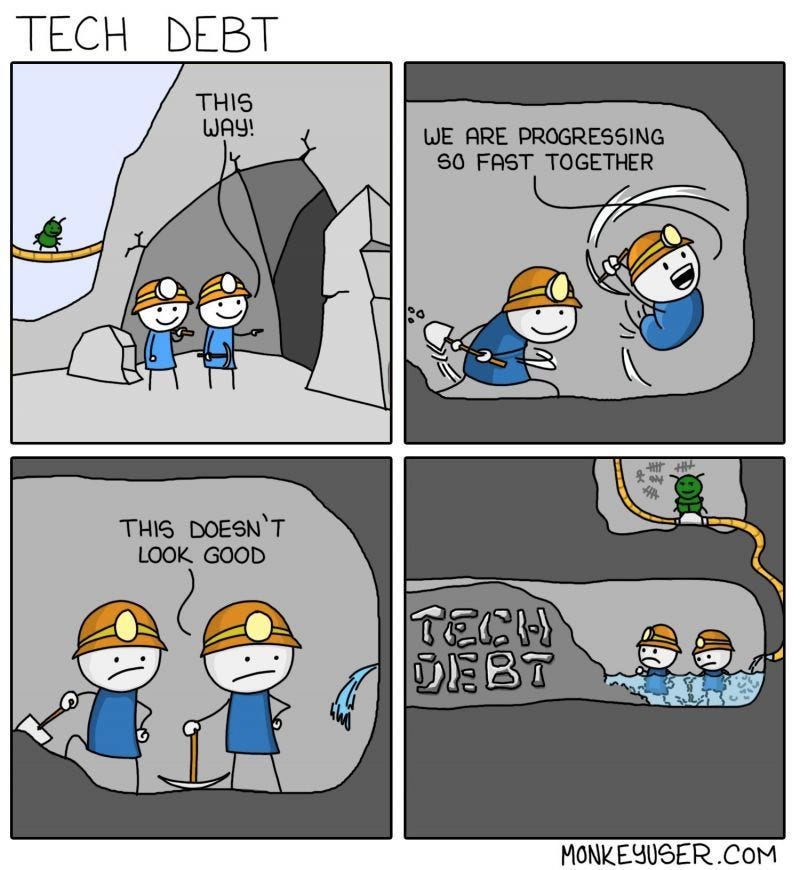

The Hidden Cost of Reactive Engineering

In a fast‑growing company, the default state of engineering is reactive. The product roadmap is packed, deadlines are tight, and the team is constantly switching context to put out the fire of the moment. In this environment, intentional technical planning feels like a luxury you can’t afford, so most teams don’t even try.

You end up:

- Shipping features continuously

- Fixing bugs as they appear

- Hoping core systems don’t fall apart

Meanwhile, technical debt quietly piles up in the background.

Why “Just Build” Isn’t Sustainable

The “just build” approach looks productive in the short term, but it carries a real, cumulative cost:

- Duplicated effort – Engineers on different teams solve the same scaling problem in different ways.

- Cross‑service friction – A simple feature request now requires changes across five services, each with its own quirks.

- Eroding velocity – The speed you were proud of six months ago starts to drop, and no one can point to a single clear reason why.

These symptoms are the slow accumulation of uncoordinated decisions. Without intentional technical planning, the organization risks a future where maintaining and extending the product becomes prohibitively expensive.

Technical Planning for Unstable Environments

Breaking out of the reactive cycle requires a shift in how we think about planning. Most frameworks are too rigid for a company where priorities can change in a week. A detailed two‑year technical roadmap is useless if it becomes obsolete a month after it’s written.

Core Principle

Adaptability, not prediction.

The aim is to create a shared understanding of technical direction so that engineers can make local decisions that still align with the broader vision. This forward‑looking view lets a team handle change without breaking everything.

Why It Matters

- Reduces duplicated effort – teams stop reinventing solutions that conflict with each other.

- Prevents architectural dead‑ends – early alignment avoids costly rework later.

- Turns planning into an accelerator – less time wasted on misaligned work, more time delivering value.

Early Warning Signs of Uncontrolled Growth

| Symptom | Impact |

|---|---|

| Longer onboarding times | Slower ramp‑up for new hires, higher training costs |

| Higher bug rates in critical modules | Decreased reliability, more firefighting |

| General friction when building new features | Lower velocity, reduced morale |

Understanding these costs is the first step toward a more adaptable, resilient technical planning process.

A Practical and Adaptable Model for Technical Planning

A good technical plan doesn’t live in a dense document no one reads. It’s a living guide that connects engineering work directly to what the business is trying to achieve. It needs to be flexible enough to change quickly, yet structured enough to provide real direction.

Define Your North Star ⭐️

Every meaningful technical initiative should be traceable back to a business goal. This isn’t about pleasing stakeholders; it’s about making sure you’re solving the right problems.

- Example: When the company decides to move up‑market and serve enterprise customers, the business goal translates into concrete technical requirements such as:

- More robust permissions

- Audit logs

- Integrations with common identity providers

Framing the work this way pulls the conversation out of the abstract and into concrete outcomes. Discussions that used to sound like “we need to refactor the authentication service” become directly tied to clear business goals—e.g., closing enterprise customers in Q3, which requires supporting SAML and role‑based access control. The reason behind the work becomes clear, and the engineering team understands why it matters, not just what needs to be done.

Building the “What”: Scope and Outcomes

With a clear “why,” prioritization becomes much simpler. You can evaluate technical work side‑by‑side with product features based on impact to company goals.

- A large refactor might not deliver immediate, visible value to users, but if it unlocks the ability to iterate 50 % faster in a core part of the product over the next year, the value is obvious.

- Make conscious trade‑offs: you might accept some technical debt in a non‑critical area to free up resources and fix a serious scalability bottleneck that threatens user growth.

Key point: Make these decisions explicitly, instead of letting them happen by accident. When defining scope, design for what you know is coming, not every possible future. Build with extensibility where you anticipate change, but avoid over‑engineering based purely on speculation.

The “How”: Planning and Execution

Execution should fit into the workflow the team already uses. When parallel processes or extra ceremonies appear, they tend to be ignored as soon as pressure ramps up.

Practices That Work Well

-

Architectural Decision Records (ADRs)

- Keep a simple Markdown file in the appropriate repository.

- Record the decision, alternatives considered, and the reasoning behind the final choice.

- This context is valuable for new team members and for your future self.

-

Involve Senior Engineers Early in the Design Phase

- Don’t wait for a 5,000‑line pull request to show up.

- Have conversations about the “how” before implementation starts—short design docs, whiteboard sessions, or a dedicated chat channel work well.

- Early involvement spreads knowledge and catches architectural issues while they’re cheap to fix.

-

Create Regular Review and Adaptation Cycles

- Treat the technical plan as a living document.

- Review it quarterly:

- What changed in the business?

- What did we learn from the last quarter’s work?

- Adjust priorities based on new information to keep the plan relevant and useful.

By anchoring every technical effort to a clear business objective, defining scoped outcomes, and embedding lightweight yet disciplined execution practices, you create a technical plan that is both actionable and adaptable.

Turning Technical Planning into an Advantage

Introducing this process doesn’t require a company‑wide initiative. You can start small—with a single team or a critical system. Pick an area of the codebase that’s a known source of pain and build a clear plan to improve it, directly connecting the effort to a product or business outcome.

At the end of the day, it’s about fostering an engineering culture where everyone feels responsible for the health of the system. When engineers understand the “why” behind the work and see a clear path to improving the codebase, they’re more engaged.

You can measure the impact directly through:

- Improved development velocity

- Greater system stability

- The ability to respond to new business opportunities without having to rebuild everything from scratch.