Extensibility: The '100% Lisp' Fallacy

Source: Hacker News

Introduction

So, I’ve seen some articles promoting Emacs‑like editors written in Lisp languages, and one of the most common arguments seems to be:

“It’s written in This Lisp and also scriptable in This Lisp, and that gives it great extensibility.”1

It’s not wrong, but I think it overlooks a few things.

By the way: Happy New Year!

1. The argument

For example, the Lem: An Alternative To Emacs? article from Irreal claims (emphasis preserved):

One thing I like about it is that it’s 100 % Common Lisp. There’s no C core; just Lisp all the way down. That makes it easier to customize or extend any part of the editor.

This argument sounds good: looking at the repository, Lem is roughly 90 % Lisp code; since the editor code and user customisation live in the Common Lisp runtime, we should be able to extend any part of the editor on the fly, right?

Or, does it really?

- Does it offer

composition-function-tableso that you can program your font ligatures from the editor’s scripting language? - Does it provide an API to define an arbitrary encoding system and the corresponding charset (

define-charset), beyond what is supported by Unicode or any existing standard? - Does it allow you to “override” its newline character (see Emacs’s display tables), so that a file is displayed all on a single line?

…

These examples are taken from some of the more obscure features in Emacs, and I could continue indefinitely. I don’t think many editors could possibly support them, as they belong to the roughly 10 % non‑pure part of a “100 % Lisp” system.

To be honest, I hate these features—they’ve haunted me ever since I started designing an IPC protocol for my Emacs clone. Yet, paradoxically, I suffered (and still suffer) because of Emacs’s extensibility, not because it lacks it.

2. There is no “100 % Lisp” ¶

For example, Steel Bank Common Lisp—a common Common Lisp runtime—is only mostly written in Lisp because it must provide threading primitives, interface with the OS, or leverage assembly code. Consequently, those low‑level bits aren’t customizable.

The same limitation applies to (graphical) editors. As with any GUI program, you’ll typically want to support:

- Font fallback

- Input methods – see the Wikipedia article on input methods

- Screen readers – see the AccessKit platform adapters description

All of these require interaction with platform‑specific APIs, making them far less customizable. Foreign Function Interfaces (FFI) can keep your core “pure”, but they cannot extend customizability beyond that boundary:

- Webviews don’t expose font‑ligature internals; CSS is the only (and limited) way to control them.

- Input methods interfere with keyboard events and are platform‑specific, making them tricky to handle.

- Screen readers are best used through a dedicated library if you need portability.

Thus, a truly “pure” Lisp program that handles all of these platform‑specific concerns is essentially impossible today. This isn’t inherently bad—it simply limits how far you can extend the system.

Nevertheless, with the right building blocks, developers often find surprising ways to work around these “non‑extensible” parts.

3. Workaround‑ish extensibility {#workaround-ish-extensibility}

Let’s first look at some approaches people adopt to extend their editors:

-

Neovim and many TUI editors don’t have native scrollbar support because they are limited to what ANSI provides.

By coloring the right‑most column withextmarkandvirt_text— see nvim‑scrollbar — it’s possible to display a pretty scrollbar for Neovim. -

Stock Emacs does not support cursor animations. Yet people have found workarounds:

- Apply patches such as the cursor‑animation patch.

- Extend Emacs Lisp with Python (e.g., the holo‑layer “jelly cursor animation”), which calls PyQt or compositor commands to control overlayed windows and display moving cursors.

-

Emacs Application Framework (EAF) lets you write GUI programs for Emacs by first implementing them in PyQt and then embedding the PyQt window into the corresponding Emacs buffer window. Not all Wayland compositors expose an API for programmatically positioning user windows, which can be a limitation for EAF.

-

EXWM (Emacs X Window Manager) – see the project on GitHub.

The moral here is that many things are more extensible than one might think. It’s amazing how people keep inventing all kinds of workarounds, and—regardless of “purity”—they all count as extensibility.

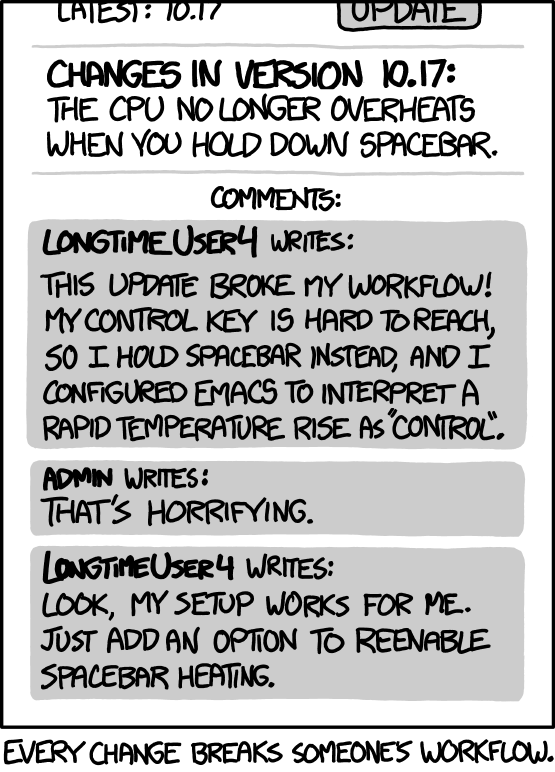

4. “Spacebar heating” extensibility

Compared to extending via work‑arounds, extending in “pure Lisp” can be both easier and harder: we are still bounded by coding conventions and existing code, and we cannot possibly extend everything without breaking something.

Overriding a single function

When exporting Org‑mode files to HTML, Org‑mode defaults to generating random HTML ID anchors. To change that, you might think you can simply override the function that generates the IDs:

(advice-add #'org-export-get-reference :around #'org-html-stable-ids--get-reference)However, Org‑mode sometimes calls org-html--reference directly, bypassing the override. You would then also need to redirect that internal function:

(advice-add #'org-html--reference :override #'org-html-stable-ids--reference)The problem with internal functions

By convention, Emacs Lisp code uses double dashes (--) to indicate that a function is internal (e.g., org-html--reference). Overriding such functions is possible, but it can be fragile: future updates may change the internal API, breaking your code.

Using el‑patch

The el-patch package lets you apply “patches” to almost any Lisp code, even deep inside a function:

;; Original function

(defun company-statistics--load ()

"Restore statistics."

(load company-statistics-file 'noerror nil 'nosuffix))

;; Patching

(el-patch-feature company-statistics)

(with-eval-after-load 'company-statistics

(el-patch-defun company-statistics--load ()

"Restore statistics."

(load company-statistics-file 'noerror

;; The patch

(el-patch-swap nil 'nomessage)

'nosuffix)))

;; Patched version (what you get after applying the patch)

(defun company-statistics--load ()

"Restore statistics."

(load company-statistics-file 'noerror 'nomessage 'nosuffix))el-patch also provides el-patch-validate, which helps ensure that your patches remain effective and do not unintentionally break things. Nevertheless, you still have to maintain all your patches when upstream code changes.

The trade‑off

Any extensible system faces these dilemmas:

- Strong encapsulation – eventually something cannot be customized.

- Full exposure – you risk breaking backward compatibility (as a maintainer) or forward compatibility (as a user).

By allowing “extension of any part of the editor,” you paradoxically make every part of your code un‑extensible, because any change can break someone’s workflow.

xkcd 1172 – workflow, aka “spacebar heating”

Emacs’s cross‑language isolation/API isn’t perfect, but it’s a huge help. If Emacs were written entirely in pure Lisp with everything extensible, a work‑in‑progress Emacs clone would be virtually impossible—especially if we want to eliminate some of the “spacebar heating” problems while preserving compatibility.

5. Extensibility Takes Effort ¶

Note: The “100 % Lisp” argument is lazy marketing. Writing a Lisp‑extended editor in Lisp doesn’t automatically make the editor more extensible. Extensibility comes from carefully designing API interfaces, learning from history, listening to user needs, and—most importantly—investing the effort and time to actually write the interfacing code.

This blog entry was adapted from a rant thread I posted to vent my shock about Emacs’s composition-function-table. Emacs is never short of wonders and surprises, especially when you’re creating your own Emacsen by replicating Emacs.

Clarification: This post is not against Lem. I’ve drawn a lot of inspiration from Lem and appreciate many of its good designs. It’s simply the most convenient example I could think of, so please pardon any perceived bias.

6. Footnotes

Table 1: For the better, right?

“I want to write a better editor.” 😄

With better accessibility, right? (silent gaze) 😓

Also, please don’t mistake maintainability for extensibility. For example, Racket has migrated from its previous C core to a Racket core powered by Chez Scheme. Quoting from Rebuilding Racket on Chez Scheme Experience Report2:

… it’s hard to put a number on these things but I can give you one number at least. This is the number of people who have been willing to modify the Racket macro expander.

This is when it was in C: two of us did it. And it’s already six people (after the C‑to‑Chez migration). Remember: the C part that was in the first 16 years and the last 16 years of that implementation, and the six people and the new implementation is just in two years. So we’re really pretty sure it’s gonna be better to maintain.

So I do believe a mostly Lispy codebase can be better maintained and potentially attract more contributors than one in C. (But Emacs is mostly Lispy anyway.)3

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution‑ShareAlike 4.0 International license.