Distributed task queue system

Source: Dev.to

The Problem

You’re running a data pipeline that processes thousands of images. Workers are humming along, everything’s fine. Then your coordinator server crashes.

- Tasks vanish.

- Two workers start processing the same image.

- Your pipeline grinds to a halt.

This is the reality of distributed systems. Machines fail. Networks partition. If you haven’t designed for failure, failure cascades into disaster.

I wanted to understand how production systems handle this, so I built a distributed task queue from scratch. Not using Redis, but implementing the coordination layer myself using the Raft consensus algorithm. The result: a system that executes Python code across multiple workers, and when a broker crashes, the others continue seamlessly with no data loss.

Architecture

The system has three components:

- Broker cluster – runs the Raft consensus protocol across three nodes. They elect a leader, and all task state is replicated to every node. If one broker crashes, the remaining two continue operating.

- Workers – stateless. They poll the leader for tasks, execute code in sandboxed subprocesses, and report results. Workers can be scaled horizontally as needed.

- Clients – submit tasks and poll for results. Both workers and clients automatically discover the current leader.

An important distinction: the Raft cluster guarantees broker failures don’t lose data. Worker failures are detected but handled differently (see later).

Task Structure

A task packages Python code for remote execution:

{

"task_id": "uuid-1234",

"task_type": "python_exec",

"payload": {

"code": "def count_words(text): return len(text.split())",

"function": "count_words",

"args": ["hello world"]

},

"status": "pending"

}The lifecycle is simple: pending → processing → completed. The broker tracks each transition, and Raft ensures all brokers agree on the current state.

Raft Consensus

The core problem: three brokers need to maintain identical task state. Simple broadcasting leads to out‑of‑order messages, dropped packets, and divergent views. Raft solves this through leader election and log replication.

Leader Election

Every node starts as a follower, waiting to hear from a leader. If a follower doesn’t receive a heartbeat within a randomized timeout (1.5–3 seconds), it becomes a candidate and requests votes from its peers.

def _on_election_timeout(self):

self.state = RaftState.CANDIDATE

self.current_term += 1

self.voted_for = self.node_id

# Request votes from all peers...The randomized timeout prevents deadlock: if all nodes timed out simultaneously, they’d all vote for themselves and no one would win. Randomization ensures one node usually starts its campaign first.

Log Replication

The leader appends commands to its log and sends them to followers. An entry is only committed once a majority of nodes have it.

def _try_commit(self):

for n in range(len(self.log) - 1, self.commit_index, -1):

# Count how many nodes have this entry

count = 1 # Leader has it

for peer in self.peers:

if self.match_index.get(peer, -1) >= n:

count += 1

# Commit requires majority (2 of 3 nodes)

if count >= majority:

self.commit_index = n

self._apply_committed()

breakThis majority requirement is what makes Raft fault‑tolerant. If the leader dies after replicating to only one follower, that entry isn’t committed yet. The surviving nodes elect a new leader and that uncommitted entry gets rolled back, preserving consistency.

A Note on Persistence

My implementation keeps everything in memory. Production Raft requires writing currentTerm, votedFor, and the log to disk before acknowledging messages. Without persistence, a crashed node could restart with a blank state, vote again in the same term, and violate Raft’s safety guarantees. This is acceptable for learning, but not for production.

Failure Scenarios

The real test of a distributed system is how it behaves when things go wrong. Below are the key scenarios.

Scenario 1: Leader Broker Dies

This is the scenario Raft is designed to handle.

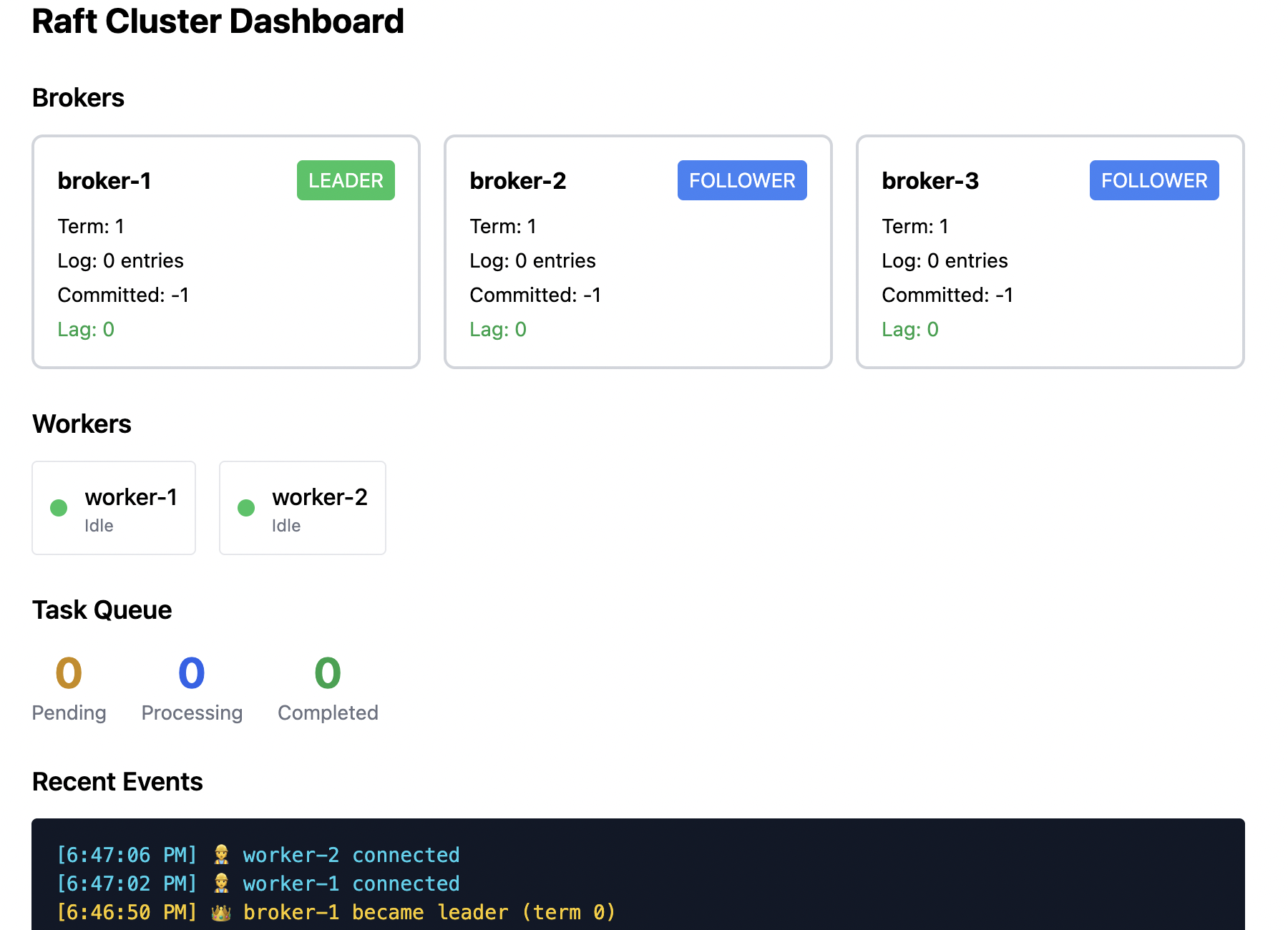

Initial state: Broker 1 is the leader; Brokers 2 and 3 are followers. Two workers are connected, processing tasks.

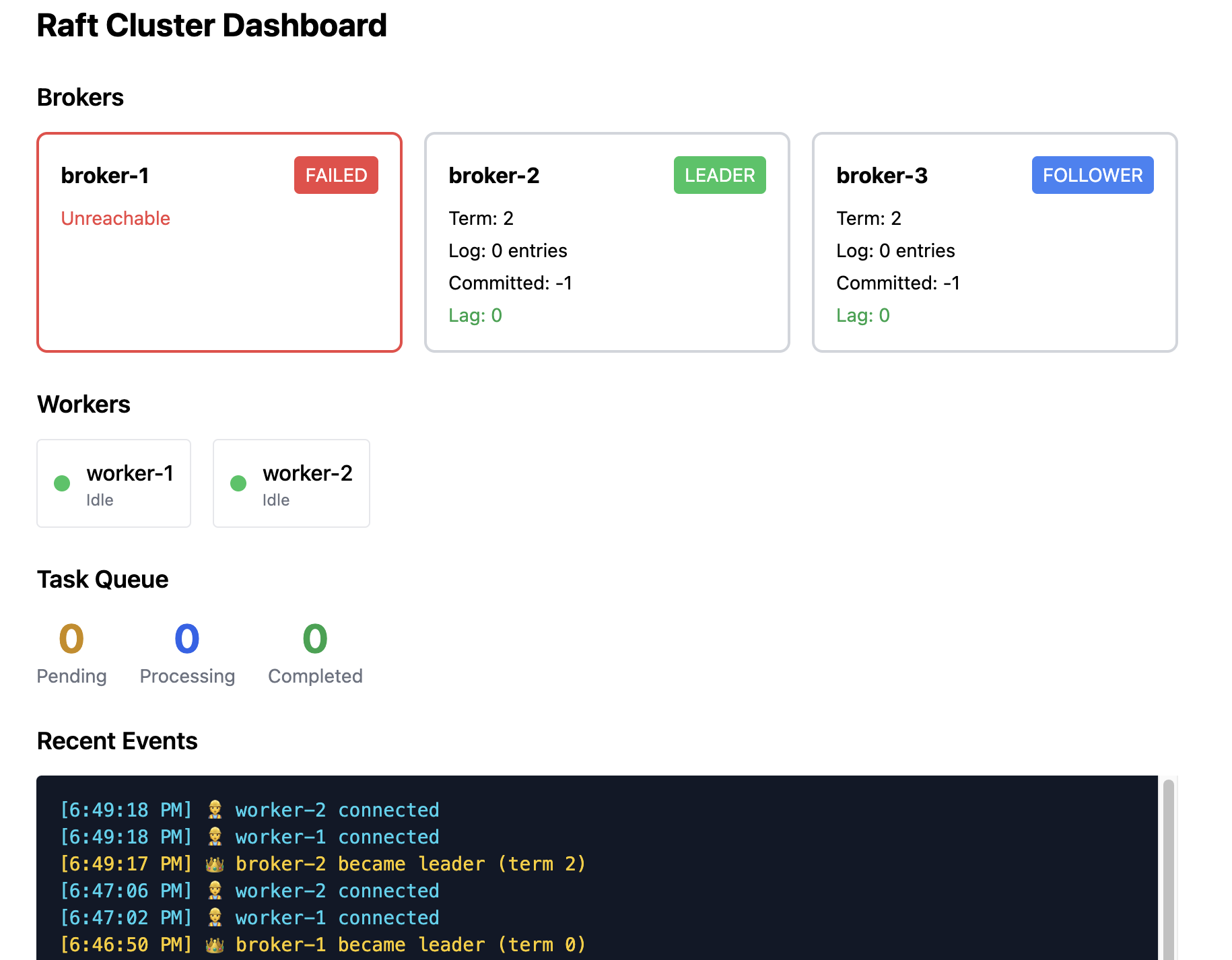

The failure: Broker 1 crashes (or gets network‑partitioned).

What happens next:

- Brokers 2 and 3 stop receiving heartbeats from Broker 1.

- Their election timers expire (within 1.5–3 seconds).

- One of them (e.g., Broker 2) times out first, becomes a candidate, and requests votes.

- Broker 3 grants its vote (Broker 1 is unreachable).

- Broker 2 becomes the new leader and starts sending heartbeats.

Worker behavior: Workers’ next request to Broker 1 fails with a connection error. They iterate through known broker addresses, query /status, discover that Broker 2 is now leader, and reconnect (typically 1–2 seconds).

Data safety: Any task that was committed before the crash is safe—it exists on a majority of nodes, and the new leader has it. Uncommitted entries (acknowledged by fewer than two nodes) are lost, but these were never confirmed to clients.

Scenario 2: Follower Broker Dies

Simpler than leader failure.

Initial state: Broker 1 is leader; Broker 3 crashes.

What happens: Almost nothing visible. The leader notices Broker 3 isn’t responding to AppendEntries, but it can still reach Broker 2. With 2 of 3 nodes alive, the cluster retains quorum and continues normally. Writes still succeed because the leader replicates to Broker 2, receives acknowledgment, and commits.

If Broker 3 returns: It rejoins as a follower, receives missing log entries from the leader, and catches up.

Scenario 3: Worker Dies Mid‑Task

The broker detects dead workers and reassigns their tasks automatically.

Initial state: Worker 1 is processing Task A. Worker 2 is idle.

Failure: Worker 1 crashes or loses network connectivity.

Broker response: The broker monitors heartbeats from workers. When the heartbeat from Worker 1 stops, the broker marks the task as pending again and places it back in the queue. Worker 2 (or any other available worker) picks up Task A and continues processing.

Result: No task is lost, and the system remains consistent despite worker churn.