Two 'Medium' Findings That Chain Into Full Infrastructure Compromise

Source: Dev.to

You know that feeling when you’re triaging security findings and you see a bunch of mediums in the backlog? They’ll get fixed eventually—probably—after the criticals, the highs, and that one feature the PM has been asking about for three sprints.

Here’s the thing: attackers don’t triage by severity. They triage by what chains together.

I want to walk through a vulnerability chain we recently documented that combines two completely unremarkable findings into something that enables authenticated phishing and persistent access to Microsoft 365 environments.

Neither finding would make anyone panic. Together, they’re a full compromise.

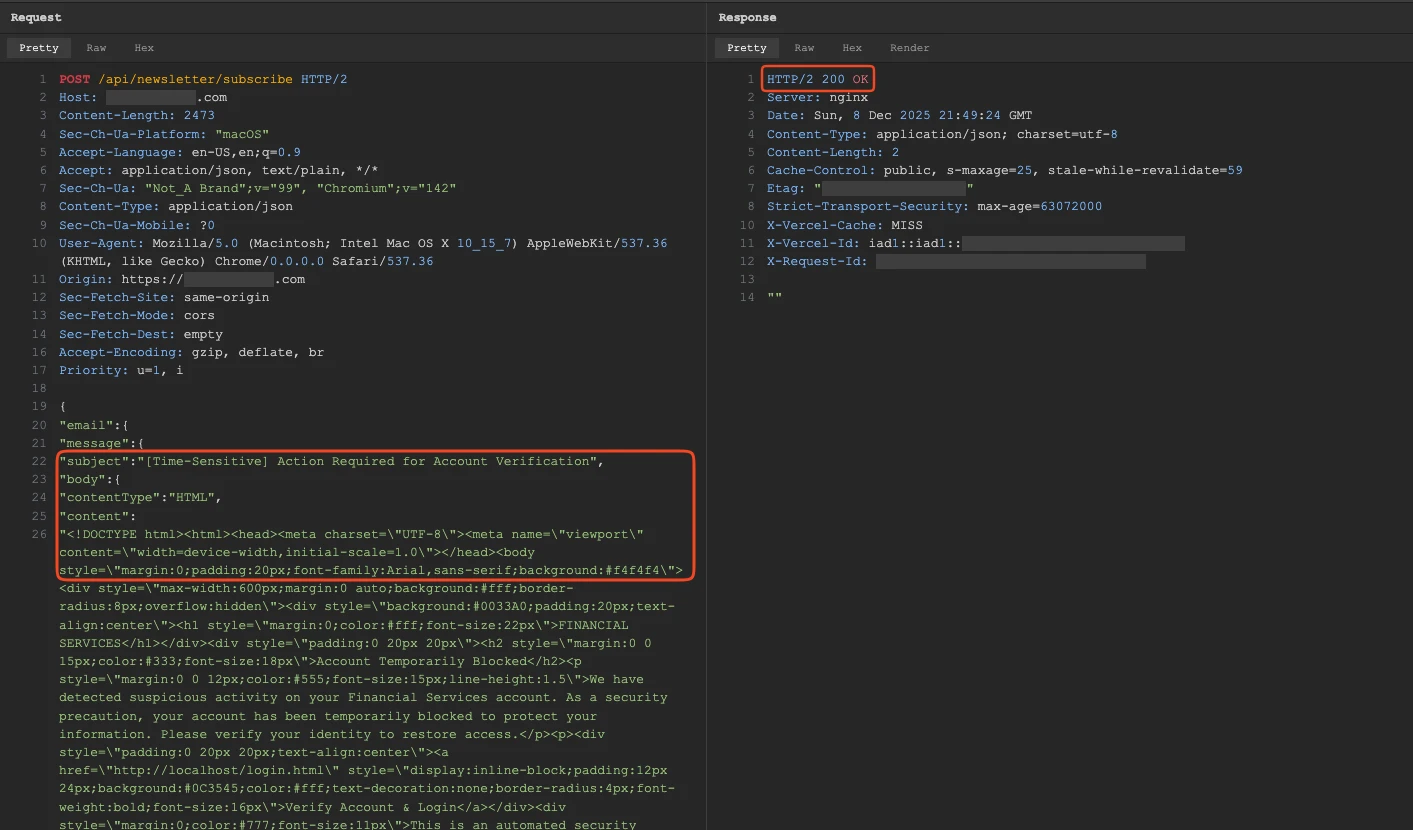

Finding #1: The Newsletter Endpoint That Does Too Much

Every web app has endpoints that send emails—newsletter sign‑ups, contact forms, password resets, transactional notifications.

These endpoints need to be public to function (that’s the point), but they also need strict input validation to prevent abuse.

Vulnerable pattern

POST /api/newsletter/subscribe HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

{

"recipient": "victim@target.com",

"subject": "Urgent: Security Alert",

"body": "...phishing content..."

}No authentication. Arbitrary recipient, subject, and HTML body.

When this request is processed, the application sends an email through the organization’s legitimate mail infrastructure. The email originates from an authorized mailbox with proper authentication.

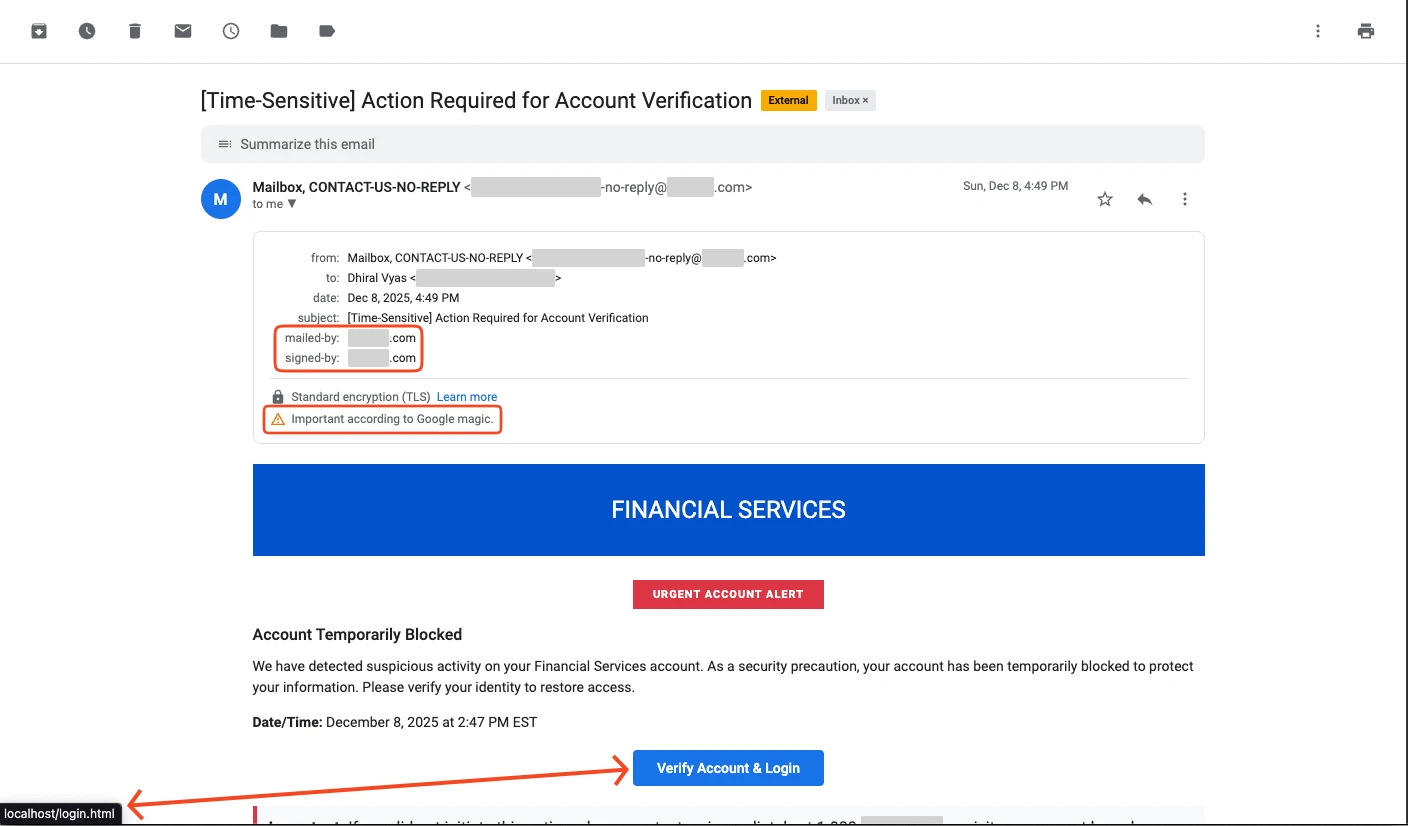

What this means in practice

- Email passes SPF, DKIM, and DMARC checks

- Sender shows the organization’s official email address

- Gmail auto‑tags it as “Important” because of the legitimate origin

- Lands in the primary inbox, not spam

You’ve just turned the target’s own infrastructure into a phishing platform.

Finding these endpoints isn’t hard

site:target.com newsletter

site:target.com "sign up"

site:target.com contactPages that aren’t linked in the main navigation are often still indexed and fully functional.

Finding #2: Error Messages That Leak Tokens

The second finding involves verbose error handling in production. You’ve seen this pattern before:

POST /api/newsletter/subscribe

Content-Type: application/json

{

"recipient": "test@test.com"

// missing required fields

}Response

{

"error": "ValidationError",

"stack": "...",

"context": {

"oauth_token": "eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9...",

"service": "graph.microsoft.com",

...

}

}Why would an error response contain OAuth tokens?

In many applications, internal services authenticate to each other using tokens stored in the application context. Verbose error handling dumps that context to the client, unintentionally exposing the tokens.

In this case, the leaked tokens were for Microsoft Graph API.

Depending on scope, that grants access to:

- Mail (read & send)

- Calendar

- Teams conversations

- SharePoint and OneDrive files

- User directory and org charts

- Sometimes Azure resources and Intune

“But tokens expire in an hour.”

True. But you can simply trigger the error again to get a fresh one. The vulnerability becomes a token dispenser—persistence without credentials.

The Chain

Stage 1: Token extraction

Attacker finds the verbose error condition, pulls a valid Graph token, and now has authenticated M365 access without triggering failed‑login alerts.

Stage 2: Reconnaissance

Using the token, they enumerate:

# Get org chart

GET https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/users

# Get user details

GET https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/users/{id}

# Get manager chain

GET https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/users/{id}/managerEmployee names, titles, projects, reporting structure, internal terminology—everything needed to craft convincing phishing.

Stage 3: Targeted phishing

They use the email endpoint to send phishing campaigns. These aren’t generic “click here to verify your account” emails; they’re crafted with real project names, accurate org structure, and internal terminology, and they come from the organization’s own mail server.

Stage 4: Escalation

Harvested credentials get the attacker deeper—admin accounts, Azure resources, production infrastructure.

Stage 5: Persistence

As long as the verbose error exists, the attacker can regenerate tokens. Credential rotation doesn’t help—the vulnerability itself is the persistence mechanism.

The Fix

Email endpoint

# Bad: accepts arbitrary input

@app.post("/api/newsletter/subscribe")

def subscribe(data: dict):

send_email(

to=data.get("recipient"),

subject=data.get("subject"),

body=data.get("body")

)# Good: strict schema, single purpose

class SubscribeRequest(BaseModel):

email: EmailStr

@app.post("/api/newsletter/subscribe")

def subscribe(request: SubscribeRequest):

# Only allow sending a predefined template to the supplied email

send_email(

to=request.email,

subject="Thank you for subscribing!",

body=render_template("newsletter_welcome.html")

)- Validate input with a strict schema (e.g., Pydantic).

- Restrict the endpoint to a single, non‑configurable purpose (e.g., only send a fixed template).

- Authenticate internal callers if possible; otherwise, enforce rate‑limiting and logging.

Verbose error handling

- Never expose internal context (especially tokens) in error responses.

- Return a generic error message to the client and log the detailed stack trace server‑side.

- Rotate and short‑lived tokens, and enforce least‑privilege scopes.

- Implement a centralized error‑handling middleware that sanitizes responses.

TL;DR

- Lock down public email‑sending endpoints – strict schemas, fixed templates, authentication, rate limiting.

- Sanitize error responses – never leak tokens or internal context.

- Monitor for unusual email‑sending activity and token‑leak patterns.

By addressing both findings, you break the chain and remove the attacker’s ability to turn your own infrastructure into a phishing platform.

Example: Subscription Endpoint

@app.post("/subscribe")

def subscribe(data: SubscribeRequest):

add_to_mailing_list(data.email)

send_confirmation_email(data.email) # fixed templateIf it’s a newsletter signup, it accepts an email address—that’s it.

For Error Handling

# Bad: dumps everything to client

@app.exception_handler(Exception)

def handle_error(request, exc):

return JSONResponse({

"error": str(exc),

"stack": traceback.format_exc(),

"context": app.state.__dict__ # tokens live here

})

# Good: generic client response, detailed server logs

@app.exception_handler(Exception)

def handle_error(request, exc):

logger.error(f"Error: {exc}", exc_info=True) # server‑side only

return JSONResponse({

"error": "An error occurred",

"request_id": generate_request_id()

})Production should never return stack traces or application context to clients.

The Takeaway

Two medium‑severity findings:

- One endpoint accepts too many parameters.

- Another endpoint returns too much information.

Your vulnerability scanner assessed these individually and rated them appropriately. The scanner isn’t wrong, but it isn’t thinking like an attacker.

Attackers don’t care about severity ratings. They care about paths.