Transaction Management: Where the Pager Becomes the Database in SQLite

Source: Dev.to

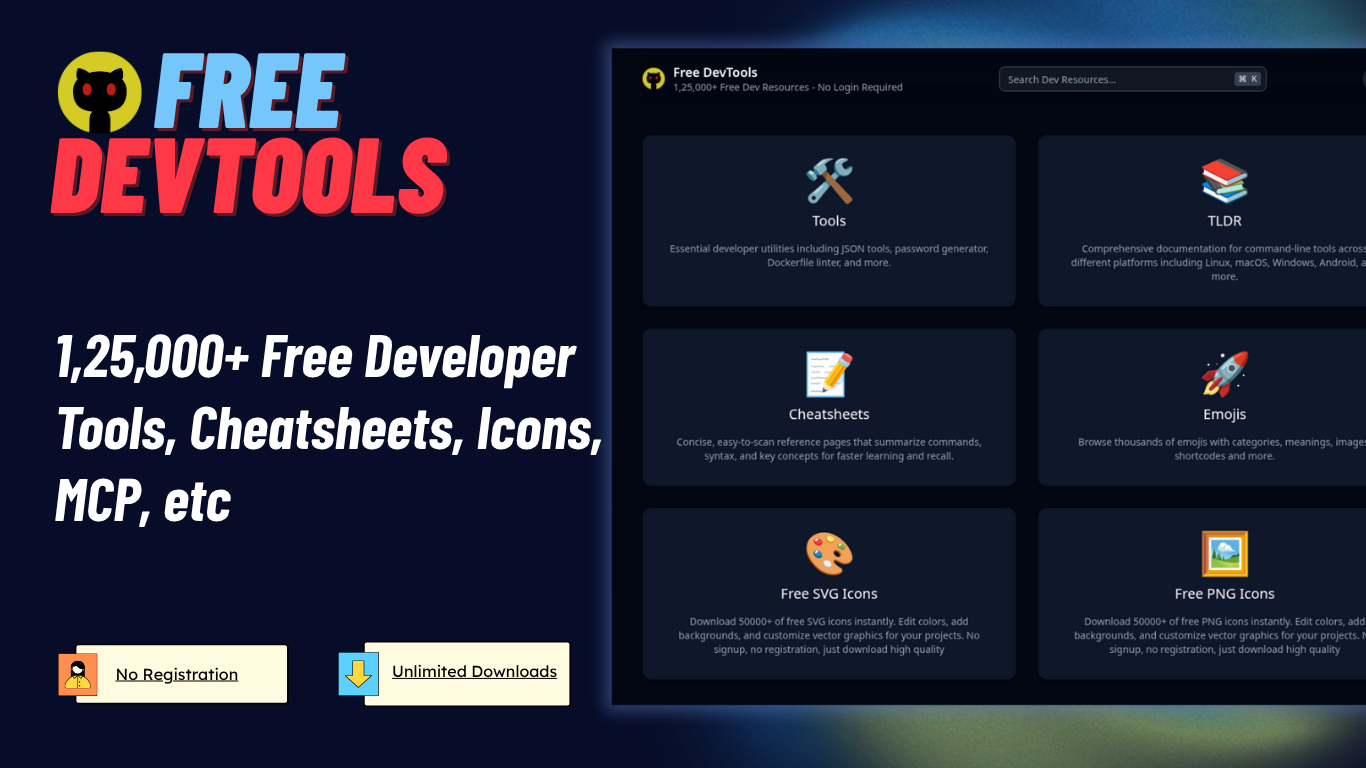

Hello, I’m Maneshwar. I’m working on FreeDevTools online, currently building “one place for all dev tools, cheat codes, and TLDRs” — a free, open‑source hub where developers can quickly find and use tools without the hassle of searching all over the internet.

Up to now, we’ve treated the pager as a cache manager, a state machine, and a disciplined gatekeeper for disk I/O.

Today’s learning makes one thing explicit:

The pager is the transaction manager in SQLite.

Locks, journals, cache state, savepoints—all of them are coordinated here.

The lock manager may perform locking at the OS level, but the pager decides when, how, and in what mode those locks are taken and released.

SQLite follows strict two‑phase locking, which gives it serializable behavior even though everything is file‑based. As with any serious DBMS, its transaction management splits cleanly into two parts:

- Normal processing

- Recovery processing

In this post we stay firmly in normal processing, the path taken when things go right.

Normal Processing: Transactions as a Controlled Flow

Normal processing is what happens during everyday execution: reading pages, modifying them, committing work, rolling back statements, and juggling savepoints.

The pager orchestrates all of this while quietly managing cache pressure in the background.

Important: None of this logic lives in the tree module.

The tree module asks for pages and mutates memory. The pager turns those requests into safe, recoverable operations.

Let’s walk through that flow.

Read Operations: Entering the Transaction World

Every interaction with a page starts the same way:

sqlite3PagerGet(page_number);- This call is mandatory, even if the page does not yet exist in the database file. If the page is beyond the current file size, the pager will create it logically.

- The first responsibility of this call is locking.

- If no lock (or only a weaker lock) is currently held, the pager attempts to acquire a shared lock on the database file.

- If it can’t because another transaction holds an incompatible lock, the read fails with

SQLITE_BUSY.

- If the shared lock is obtained, the pager proceeds with the cache read:

- If the page is already cached, it’s pinned and returned.

- If not, the pager finds a free slot (possibly evicting another page) and loads the page from disk.

At this point the tree module receives a pointer to an in‑memory page image, followed by a chunk of private space. That private space is always zero‑initialized the first time the page enters memory and is later repurposed by the tree layer for its own bookkeeping.

Deferred Recovery: Fixing the Past Before the Present

There’s an important side effect hidden inside the first shared lock acquisition.

When the pager acquires a shared lock for the first time on a database file, it checks for a hot journal file. The presence of such a journal means something went wrong earlier—a crash, power loss, or abrupt termination during a previous transaction.

If a hot journal is found, recovery happens right here:

- The pager rolls back the incomplete transaction.

- Restores pages using the journal.

- Finalizes the journal file.

Only after the database is back in a consistent state does sqlite3PagerGet return to the caller.

Result: SQLite can promise you never read from a corrupted database, even after a crash.

Cache Pressure During Reads

Sometimes simply reading a page forces a write.

- If the cache is full and the pager needs a slot for the requested page, it must select a victim.

- If that victim page is dirty, the pager flushes it to disk before reuse.

This happens transparently during normal processing and is one of the reasons cache management and transaction management are inseparable in SQLite.

Write Operations: Declaring Intent Before Action

Writes are where discipline matters.

- The client must already have the page pinned via

sqlite3PagerGet. - Then it must call:

sqlite3PagerWrite(page);sqlite3PagerWrite does not write anything to disk; it merely signals intent.

- The first time any page in a transaction is made writable, the pager tries to acquire a reserved lock on the database file. This lock announces: “I plan to write, but I haven’t yet.”

- Only one pager can hold this lock at a time. If another transaction already holds a reserved or exclusive lock, the call fails with

SQLITE_BUSY.

Successfully acquiring the reserved lock marks a critical transition: a read transaction becomes a write transaction.

- The rollback journal is created and opened.

- The initial journal header is written, recording the original size of the database file.

From this point onward, the pager is responsible for being able to undo everything.

Journaling Pages: One Before‑Image Is Enough

To make a page writable, the pager writes the page’s original contents into the rollback journal as a new log record. This happens once per page per transaction.

- Newly created pages don’t need to be logged—there’s no old state to restore.

After journaling:

- The page is marked dirty.

- Changes stay in memory.

- The database file remains untouched.

This guarantee means that while a transaction is updating pages in cache, other transactions can continue reading the database file safely, because it still reflects the old, committed state.

In‑Cache Mutation and Isolation

Once sqlite3PagerWrite returns, the tree module can modify the page freely—once, twice, or a hundred times. The pager does not need to be notified again.

Changes accumulate in memory, protected by:

- The reserved lock

- The rollback journal

- The pager’s state machine

No cache flush is triggered by writes alone; disk I/O is deliberately deferred. This is how SQLite balances performance with durability.

Isolation and Performance without Complex Concurrency Control

During normal processing:

- Pages are read under shared locks

- Writes escalate to reserved locks

- Before‑images are safely journaled

- All modifications live in cache

- The database file remains pristine

Nothing is committed yet. Nothing is flushed yet.

But everything needed for recovery is already in place.

What’s Next

In the next post, we’ll follow this transaction to its natural conclusions:

- Cache‑flush mechanics

- Commit operations (and why they happen in phases)

- Statement‑level transactions and sub‑transactions

My experiments and hands‑on executions related to SQLite will live here:

lovestaco/sqlite – SQLite examples

References

-

SQLite Database System: Design and Implementation – Sibsankar Haldar (n.d.)

-

👉 Check out: FreeDevTools

Any feedback or contributions are welcome!

It’s online, open‑source, and ready for anyone to use.

⭐ Star it on GitHub: HexmosTech/FreeDevTools