The Legacy of Undersea Cables

Source: Hacker News

Former assistant curator trainee Jasmin Taylor explores how the history and unheard voices behind the undersea telegraph cable are replicated in modern communication technology.

Wireless myth vs. reality

Wireless technology and data stored in “The Cloud” may lead you to think information is pinged around the globe via satellites. Only a very small portion is. Instant communication—texts, phone calls, and websites—is made possible by copper and fibre‑optic undersea cables that carry data between countries.

- 97 % of internet traffic travels through these cables.

- All the undersea fibre‑optic cables worldwide span ≈ 1.2 million km (750 000 mi)—enough to wrap around Earth 30 times!

Subsea fibre‑optic cables are critical infrastructure that support our global networks. They are essential for communication, commerce, government, and military functions because they securely transport messages and information. The importance of undersea cables means that control or disruption of them can have serious political and economic implications.

A Victorian artefact

Parcel‑gilt Victorian silver rosewater fountain designed as a table centrepiece and made for the United Kingdom Electric Telegraphic Company in 1870.

The birth of undersea telegraphy

Undersea cables were initially created in the late 1800s to improve the speed of the electric telegraph—the precursor of all current telecommunication systems. The telegraph sent information by making and breaking electrical connections in Morse code, allowing messages to travel far faster than physically transporting them.

The materials used to create telegraph cables, and the countries they connected, reflected Britain’s imperial global power.

- 1851 – The first international telegraph crossed the English Channel, linking Britain to France. Developed by brothers John and Jacob Brett and Thomas Crampton, the cable was coated in gutta‑percha.

- Gutta‑percha – a natural plastic derived from the sap of trees native to present‑day Peninsular Malaysia (historically Malaya).

“It was introduced to Europeans in 1656 when John Tradescant the Younger, a botanist, collector and royal gardener, brought samples back to London after one of his travels to a British colony.”

In 1832 Europeans learned how to fashion gutta‑percha into objects: it could be softened in hot water, moulded, then cooled to harden. Its waterproof nature made it an ideal cable insulator. Gutta‑percha remained the dominant insulating material until the discovery of polythene in the 1930s.

Gutta‑percha armorial moulding, 1850‑1900.

The Transatlantic breakthrough

The laying of the Britain‑France telegraph cable preceded a partnership between the USA and Britain, eventually leading to the successful laying of the Transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866. This achievement:

- Revolutionised global communication.

- Strengthened political ties between the two nations.

- Gave countries the ability to control the flow of information, increase geopolitical influence, and reinforce imperial power.

Sample of transatlantic cable, 1865‑66.

Environmental cost and overlooked expertise

While Britain and the USA reaped the benefits of their cable successes, the trees that provided gutta‑percha were driven toward extinction. Making a single cable required extremely large quantities of the material; by the 1890s the cable industry was using 4 million lb of gutta‑percha per year.

- The demand was unsustainable, prompting Britain to establish commercial plantations in Malaya.

- Malay knowledge was essential for locating and extracting gutta‑percha from jungle trees.

- Britain used its imperial reach to secure a monopoly on cable manufacturing, attributing the success of the cable to the West while largely overlooking the practical knowledge and contributions of the Malay people.

From telegraph to fibre‑optic: a legacy of imperial routes

Although telegraphs are now obsolete, modern fibre‑optic cables are laid on similar routes to the historic telegraph system—legacies of imperialism that continue today.

As network signals (electrical waves that carry data between devices) move between continents, they intersect with “networked islands” such as New Zealand, Guam, Bermuda, Puerto Rico, and Cyprus. These islands are places utilised for running network signals and are often former colonies or territories of Britain or the USA. Their inclusion allowed the metropoles to:

- Communicate more easily with their territories.

- Protect the cables and the information transmitted through them from foreign interference.

Case study: Fiji

One of these previously occupied and networked islands is Fiji. The island was incorporated into Britain’s “all‑red line”, a system of cable networks linking all parts of the British Empire without ever touching foreign soil.

- 1902 – The first cable was laid in Fiji.

- 1950‑60s – Fiji became an established hub of telecommunications development.

Two shore‑end cable samples and telegraph recorder tape, 1926.

Take‑away

- Undersea cables—both historic telegraph lines and modern fibre‑optic routes—are the backbone of global communication.

- Their construction, maintenance, and routing are deeply entwined with imperial histories, resource extraction, and overlooked expertise (e.g., Malay contributions to gutta‑percha production).

- Recognising these hidden narratives helps us understand the political, economic, and environmental dimensions of the networks we rely on today.

Elegraph Recorder Tape, 1926

Recovered from Suva Point Cable House, Fiji, in 1956.

Britain’s colonial presence in Fiji attracted private companies that wanted to lay cables in the ocean and route international signals through isolated islands. The companies benefited from protection against foreign cable interference, while Britain strengthened communication throughout its empire.

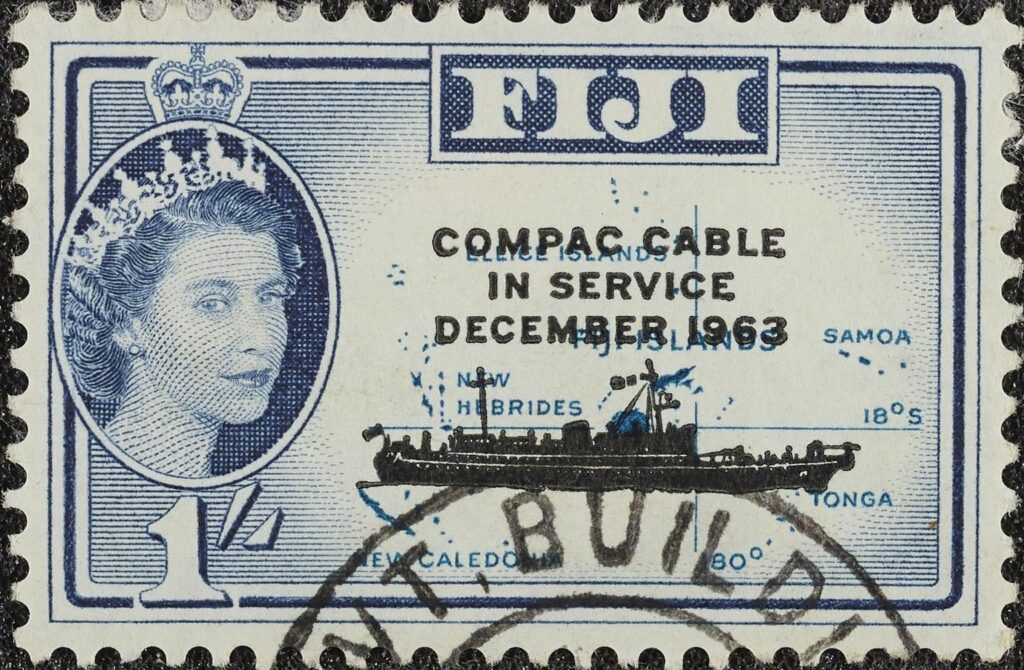

1 shilling stamp (used) – “COMPAC CABLE IN SERVICE, DECEMBER 1963”

From sharks biting through cables and interrupting network connections to natural disasters severing multiple cables in seconds, cable vulnerabilities take various forms.

Cables are also susceptible to intentional damage, most recently seen in the 2024 Baltic Sea submarine‑cable disruptions when several undersea cables were severed. This type of tampering is why telecommunication companies sought to lay cables in islands like Fiji, which were under Western colonial occupation: it added a layer of defence against interference.

Section of submarine telegraph cable (1873) – recovered 1906

This was no longer the case in Fiji after it gained independence from Britain in 1970. A rise in political tension and coups caused telecommunications companies to abandon future cable plans there.

Fiji spent the 1990s regaining stability and improving its economy. Today there are six fibre‑optic cables in Fiji, and Google has pledged to lay a further two in 2026.

The cables are part of the Pacific Connect initiative—a collaboration with several partners to increase the resilience and reliability of digital connectivity in the Pacific by linking Pacific islands to America and Japan.

Ownership of subsea cables

- Private organisations now own ≈ 99 % of the world’s cables.

- The remaining ≈ 1 % is owned (or partially owned) by government entities.

Specimen of fibre‑optic submarine telephone cable (c. 1966‑1983)

Today, fibre‑optic cables are essential to global digital communication. Because of this, as political relationships between countries change, subsea cables can become targets. At the same time, they can bring economic development to the places they land. With increased digital services, more people can access career opportunities, upskill, and businesses and public‑sector organisations can better serve and connect communities.

Explore more: Discover additional stories about the history of communication technologies in the [Information Age] gallery at the Science Museum.