Part 9: Generating Simba Network with Rust

Source: Dev.to

Image → CSV Encoder / Decoder

I found a black‑and‑white drawing of a lion cub and used the following script to convert the pixels to CSV numbers (and back again):

Image to CSV Encoder / Decoder

Once the CSV was generated, I fed it to the neural network with my usual Python training script.

Helping the Machine to Draw

The script struggled at several points, so I added a few fixes to help the network learn how to draw Simba.

The Large‑Image Issue

- Original size: 474 × 474 px – caused training to be unbearably slow.

- Adjusted size: 200 × 200 px – keeps training time reasonable.

The Machine Crash & Restart

Occasional overheating caused the machine to crash, and training would restart from scratch each time—a huge waste of time and resources.

Solution: Added a save / load checkpoint mechanism so training can resume from the last saved model.

The Error‑Oscillation Problem

No matter how small the learning rate, the loss got stuck in an oscillation loop. I tried an extremely tiny learning rate (e.g., 0.000001), but training became impractically slow.

Instead, I implemented cosine annealing to gradually decrease the learning rate:

# Cosine annealing learning‑rate schedule

decay_factor = 0.5 * (1 + math.cos(math.pi * i / (epochs + epoch_offset)))

current_lr = lr_min + (lr_max - lr_min) * decay_factorThis produced smooth, steady learning.

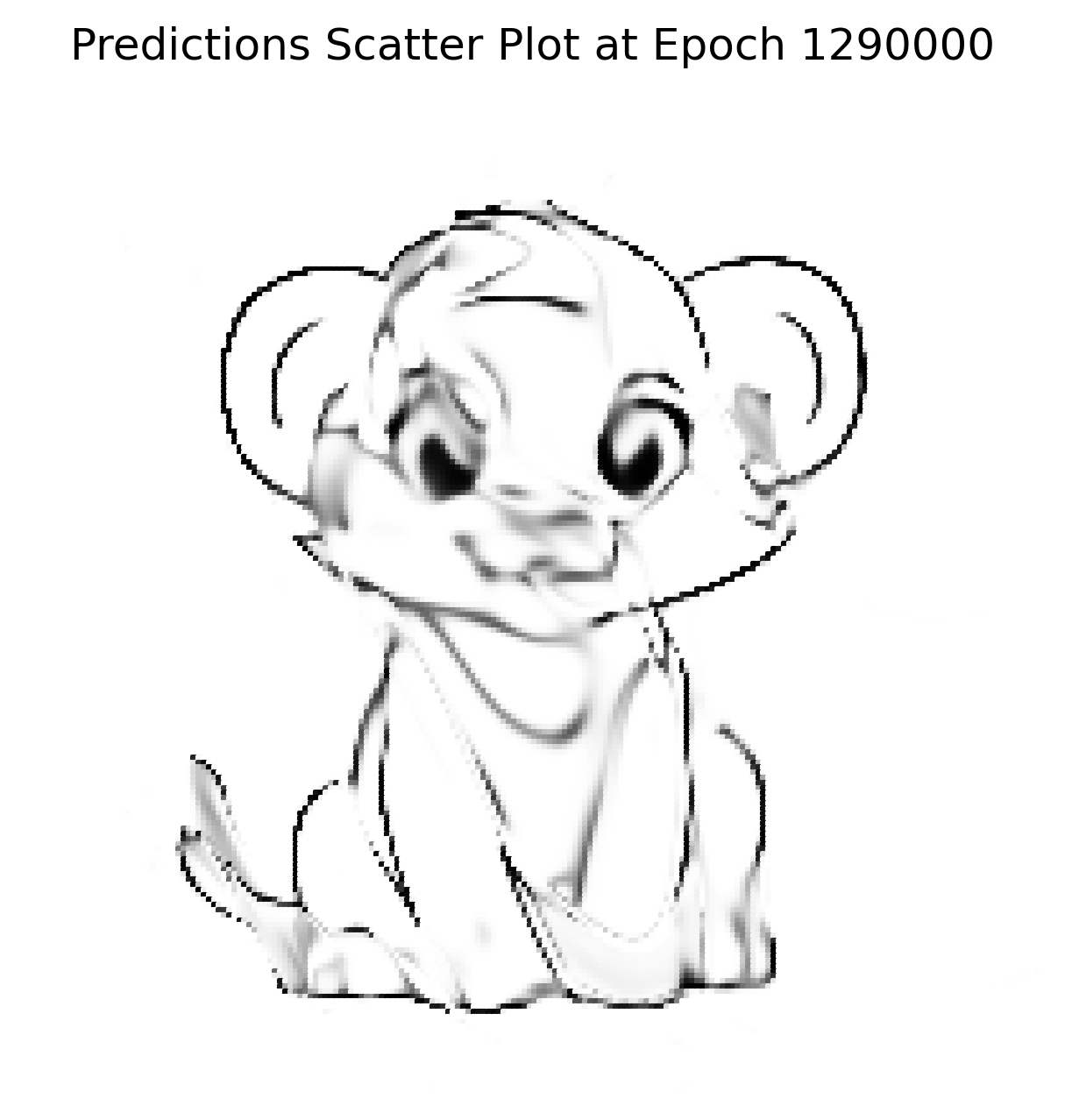

The Result: Art Through Math

After fixing the issues and running the network for ≈ 1.2 M iterations (about 4 h on my machine), the generated output was very close to the input image.

The input represents a highly complex, high‑dimensional function—far beyond a simple XOR gate or logistic‑regression dataset. This experiment demonstrates the Universal Approximation Theorem: a neural network can represent (almost) any continuous function.

Original Image

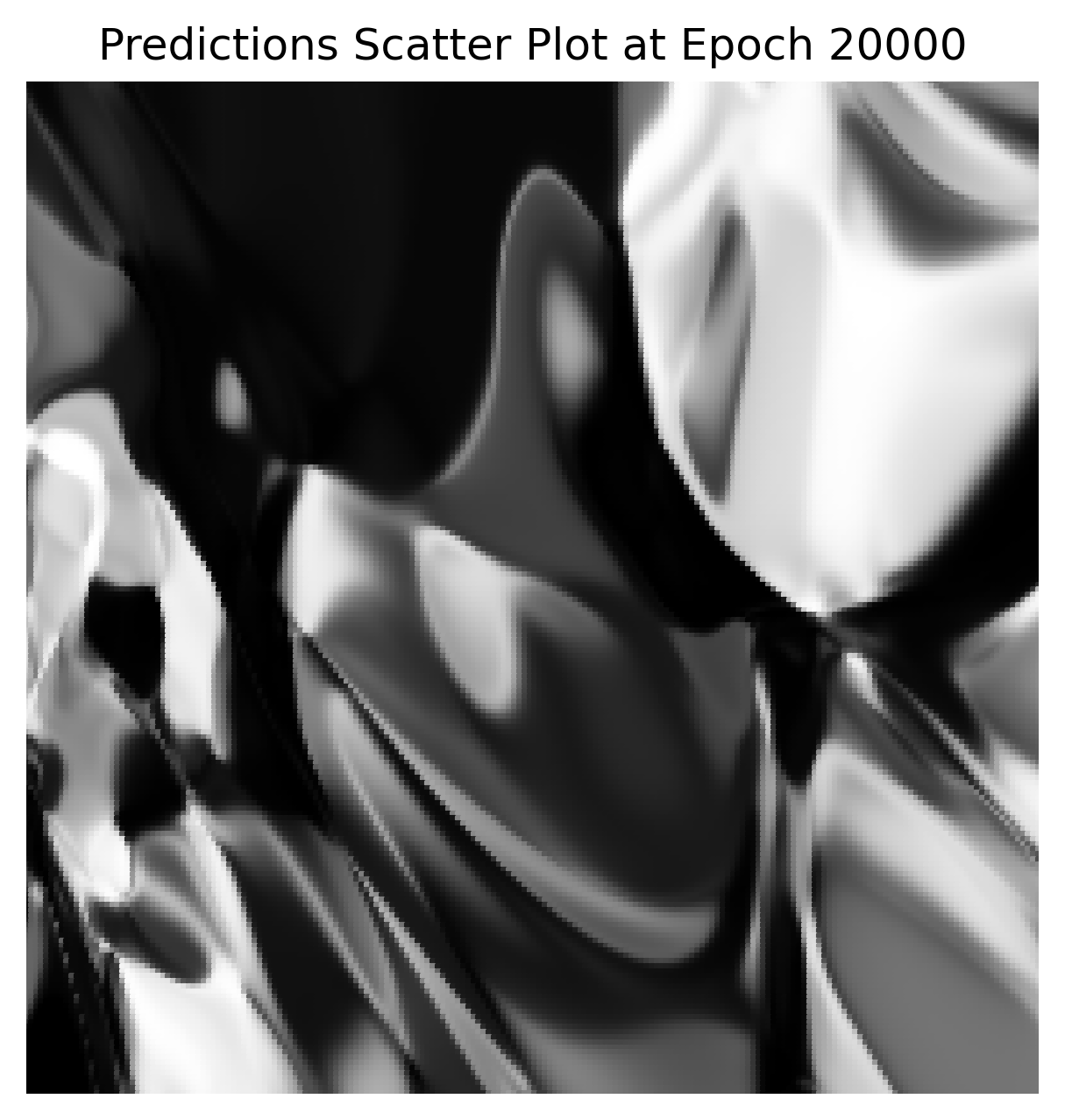

Initial Static (Random Weights)

Final Reconstruction (200 × 200)

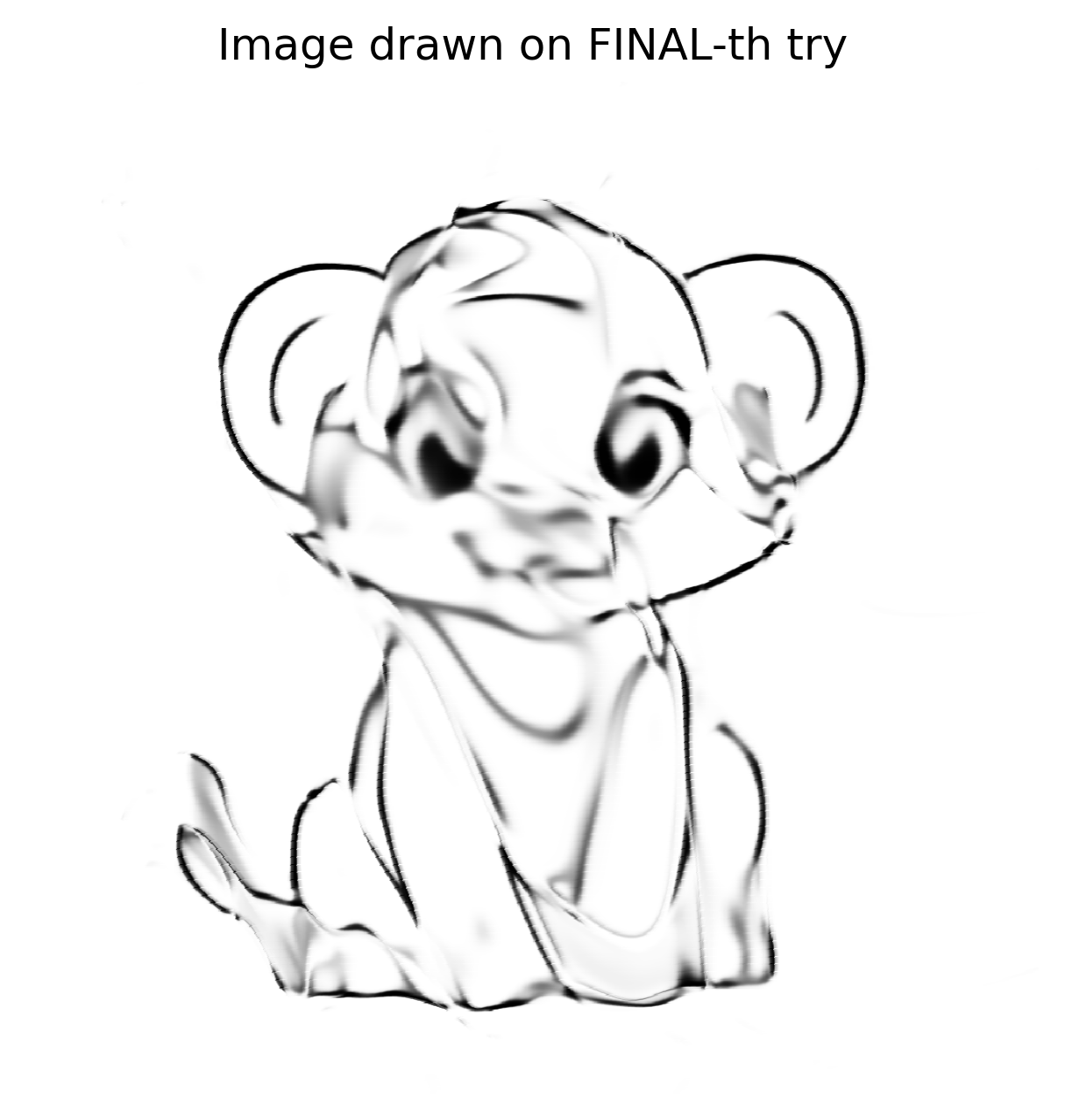

Reconstruction on Higher Resolutions

Using the learned weights, the network was tested on various canvas sizes (50 × 50, 512 × 512, 1024 × 1024, etc.). It consistently reproduced the image, indicating that it learned the underlying function rather than memorising individual pixels.

1024 × 1024 reconstruction

Because the network learned the mathematical concept of the lines, the 1024 × 1024 version isn’t pixelated like a naïve zoom; it looks as if the network is redrawing the masterpiece on a larger canvas.

Validation & Next Steps

I built a highly complex, inefficient, and expensive image‑scaler. The result is satisfying but not perfect—it proves the point, but I want higher fidelity.

After posting the result on Reddit, a user suggested trying SIREN (Sinusoidal Representation Networks).

- SIREN uses sine activations instead of ReLU/Tanh.

- It excels at implicit neural representation, a technique very similar to what I was attempting.

I have now implemented a SIREN in Python with the hope of achieving even better reconstructions. Stay tuned for the next post!

The Rust Comeback

The Python prototype showed fruitful results, reigniting my enthusiasm to tackle the problem in Rust. After a brief pause, I spent another week preparing the Rust implementation:

- Created a

Tensortrait and moved all defined methods into it. - Implemented a

CpuTensorstruct with theTensortrait. - Implemented a

GpuTensorstruct with theTensortrait.

The Initial Shock

The GPU tensor took 90 + seconds to run the same network that completed in 8 seconds in Python. Profiling with Nsight Systems (nsys) revealed that most of the runtime was spent in memory allocation and deallocation, not in CUDA kernels.

CuPy avoids this overhead by using a custom memory‑pool implementation. I needed a similar solution for Rust. The cust crate does not expose a direct pool API, but the CUDA driver provides one, re‑exported under cust::sys. After considerable trial‑and‑error, I integrated a working memory‑pool helper.

Memory‑Pool Helper (Rust)

pub fn get_mem_pool() -> CudaMemoryPool {

// Get the first CUDA device

let device = Device::get_device(0).unwrap();

// Create a memory pool for the device

let mut pool = std::ptr::null_mut();

let pool_props = CUmemPoolProps {

allocType: cust::sys::CUmemAllocationType::CU_MEM_ALLOCATION_TYPE_PINNED,

handleTypes: cust::sys::CUmemAllocationHandleType::CU_MEM_HANDLE_TYPE_NONE,

location: cust::sys::CUmemLocation {

type_: cust::sys::CUmemLocationType_enum::CU_MEM_LOCATION_TYPE_DEVICE,

id: 0,

},

win32SecurityAttributes: std::ptr::null_mut(),

reserved: [0u8; 64],

};

// Create the pool (unsafe because it calls the CUDA driver API)

unsafe { cuMemPoolCreate(&mut pool, &pool_props) };

// Reserve a large chunk of memory once, then return it to the pool.

let reserve_size: usize = 2048 * 1024 * 1024; // 2 GiB

let mut reserve_ptr: CUdeviceptr = 0;

unsafe {

// Allocate from the pool (synchronous the first time)

cuMemAllocFromPoolAsync(

&mut reserve_ptr,

reserve_size,

pool,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

);

cuStreamSynchronize(std::ptr::null_mut());

// Immediately free it back to the pool for reuse

cuMemFreeAsync(reserve_ptr, std::ptr::null_mut());

cuStreamSynchronize(std::ptr::null_mut());

}

println!("Memory pool created for device {}", device.name().unwrap());

CudaMemoryPool {

pool: Arc::new(Mutex::new(UnsafeCudaMemPoolHandle(pool))),

}

}Running this helper in a simple main program showed thousands of memory blocks being allocated and deallocated in milliseconds. The one‑time pool creation cost is negligible compared to the speed gains on subsequent allocations.

Integration in GpuTensor

After adding the helper, I kept the pool alive using Arc<…> and wrapped all device allocations to go through it. Initially the performance issue persisted, so I investigated further.

Copy, Paste… And… Compiler Error

The pool needed to be stored globally, similar to the CUDA context, to survive for the program’s lifetime. I also discovered that the CUDA wrappers themselves were still using the default allocator, so I had to replace those calls with pool‑based allocations.

Handling raw pointers became necessary. Below is a trimmed example of a custom device buffer that links host memory and device memory:

impl Drop for CustomDeviceBuffer {

fn drop(&mut self) {

let pool = match &GPU_CONTEXT.get() {

// …

};

// …

}

}(Implementation details omitted for brevity.)

Reflections

- SIREN vs. Sigmoid – Switching to sine activations gave sharper reconstructions, but required a steep learning curve.

- Python → Rust – The Python prototype built confidence; Rust exposed performance pitfalls, especially around memory management, prompting a deep dive into CUDA internals.

- Memory Pools – Using CUDA’s memory‑pool API via

cust::sysdramatically reduced allocation overhead. Keeping the pool alive (Arc<…>) and routing all device allocations through it was key. - Raw Pointers – Safe handling is possible with careful

Dropimplementations and proper synchronization.

Example: Obtaining the CUDA Pool from the Global Context (Rust)

// Retrieve the pool (panics if the context or pool is missing)

let pool = GPU_CONTEXT

.get()

.expect("No GPU context set")

.pool

.as_ref()

.expect("CUDA not initialized or GPU pool not set");Example: Freeing a Device Pointer (Rust)

// `pool` is the `Arc<MemoryPool>` obtained above

let _ = pool.free(self.as_device_ptr().as_raw());Example: Allocating a Custom Device Buffer Through the Pool (Rust)

use cust::{

memory::{DeviceBuffer, DevicePointer},

prelude::*,

};

use std::{

mem::size_of,

sync::Arc,

};

/// Wrapper around a `DeviceBuffer` that is always allocated from the CUDA memory pool.

pub struct CustomDeviceBuffer<T> {

pub device_buffer: DeviceBuffer<T>,

}

impl<T> CustomDeviceBuffer<T> {

/// Allocate a buffer of `size` elements using the global CUDA memory pool.

pub fn get_device_buffer(size: usize) -> Self {

// 1️⃣ Grab the pool (panic if it isn’t available)

let pool: Arc<cust::memory::MemoryPool> = GPU_CONTEXT

.get()

.expect("No GPU context set")

.pool

.as_ref()

.expect("CUDA not initialized or GPU pool not set")

.clone();

// 2️⃣ Compute the byte size, checking for overflow

let byte_size = size

.checked_mul(size_of::<T>())

.expect("Requested allocation size overflowed");

if byte_size == 0 {

panic!("Attempted to allocate a zero‑size buffer");

}

// 3️⃣ Allocate raw memory from the pool

let raw_ptr = pool

.allocate(byte_size)

.expect("CUDA memory‑pool allocation failed");

// 4️⃣ Turn the raw pointer into a `DevicePointer<T>`

let dev_ptr = unsafe { DevicePointer::from_raw(raw_ptr as *mut T) };

// 5️⃣ Build a `DeviceBuffer<T>` from the raw parts (unsafe but safe here)

let device_buffer = unsafe { DeviceBuffer::from_raw_parts(dev_ptr, size) };

// 6️⃣ Return the wrapped buffer

Self { device_buffer }

}

}Key points

- Safety – The only

unsafeblocks are the conversions from raw pointers toDevicePointerand from raw parts toDeviceBuffer. All pre‑conditions (non‑zero size, correct alignment, successful allocation) are verified beforehand. - Memory‑pool usage – Allocation is performed via

pool.allocate, guaranteeing that the buffer participates in the pool’s reuse strategy. - Error handling –

expectis used for brevity; production code would return aResult<_, cust::error::CudaError>instead of panicking.

The Raw Pointer Size Issue

What happened

- I allocated memory based only on the length of the array.

- I forgot to multiply by the byte width of the element type.

For an array of f32 with length 1, I allocated 1 byte instead of the required 4 bytes.

Fix

// Incorrect allocation (length only)

let size = length; // → 1 byte for f32[1]

// Correct allocation (length × element size)

let size = length * std::mem::size_of::<f32>(); // → 4 bytes for f32[1]After correcting the allocation, the code compiled and ran successfully, though execution time did not improve.

The Hidden Bug

Tensor::ones was recreating a Vec of ones and copying it to the device at every epoch. I replaced this with a GPU kernel that fills memory directly:

extern "C" __global__ void fill_value(float *out, int n, float value)

{

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

out[idx] = value;

}

}cuBLAS Wrapper (Rust)

Result {

let m = self.shape[0] as i32;

let k = self.shape[1] as i32;

let n = rhs.shape[1] as i32;

let total_elements = (m * n) as usize;

let result = get_device_buffer(total_elements);

let alpha = T::one();

let beta = T::zero();

unsafe {

cublasSgemm_v2(

Self::_get_cublas_handle(),

cublasOperation_t::CUBLAS_OP_N,

cublasOperation_t::CUBLAS_OP_N,

n,

m,

k,

&alpha.f32(),

rhs.device_buffer.as_device_ptr().as_raw() as *const f32,

n,

self.device_buffer.as_device_ptr().as_raw() as *const f32,

k,

&beta.f32(),

result.as_device_ptr().as_raw() as *mut f32,

n,

);

}

let result_shape = vec![self.shape[0], rhs.shape[1]];

Ok(Self::_with_device_buffer(result_shape, result))

}The cuBLAS version did not yield a speed‑up because the matrix sizes were modest; cuBLAS shines with very large matrices.

Conclusion

The journey was long and full of setbacks, but each obstacle taught me valuable lessons about neural‑network design and low‑level GPU programming in Rust. I now have a functional Rust Tensor library that leverages CUDA memory pools, custom device buffers, and (optionally) SIREN networks for high‑quality image reconstruction.

Note: The XOR test dataset is not a concern here; the solution works, and I will definitely benefit when I tackle the much larger image‑reconstruction task.