Finding leadership in times of crisis

Source: Dev.to

It’s only fitting (I actually find it a bit comical) that I should begin writing here with such a topic. Being in a state of crisis can sometimes be hard to identify, but once seen, it cannot be unseen. Its nagging signs and confirmations immediately begin to get in the way of productivity and even sanity. Feelings of hopelessness, indifference and carelessness begin to show and the hopes for a brighter future can sometimes fade. This article takes a methodical approach to finding leadership in crisis situations, as well as providing tips and ideas on how to better prepare for such unpredictable future circumstances.

Note: The topic of crisis situations is very broad and, though it may be helpful elsewhere, the information provided here is primarily focused on software engineering. This article was originally published on Medium.

Times of crisis

One of the definitions for crisis in the Merriam‑Webster Dictionary that I find particularly applicable is:

an unstable or crucial time or state of affairs in which a decisive change is impending

But being in a state of crisis is really quite a subjective matter. It is up to the individual, team, or organization to identify it (even if this means getting external help). So how do you come to the conclusion that you or your organization are in fact in a state of crisis?

Identifying a crisis situation

Several factors should be considered when assessing a situation. In my experience, the groups listed below are the most fundamental to consider when analyzing a situation. Bear in mind that the individuals or team performing the assessment do not necessarily need to be those who will remedy the situation.

Urgency and time constraints

There are usually two overarching types of crisis situations:

- Unpredictable crises – e.g., computer failure, a dependency system being hacked or taken down for an unexpected reason, etc. To put it into perspective, some of these events cause the 1 % out of a typical 99 % uptime SLA (Service Level Agreement).

- Predictable crises that were ignored – e.g., an expected hike in application usage during a particular upcoming shopping season, but the organization responsible for the application does not take the necessary steps to prepare for it.

The main difference between these two types is time before “a decisive change is impending”: time to decide whether the event is in fact a crisis, and time to decide how to act (including the decision to ignore).

Impact and escalation potential

I think the name says it all, but I’ll list some common questions to help determine the severity:

- Is the crisis life‑threatening or business‑threatening?

- How many clients are affected?

- What is it going to cost us, and what are the running costs until the situation is mitigated?

- How visible is the crisis? Will it hurt our brand, and in what way?

Uncertainty and lack of direction

This type of crisis is usually hard to identify because it is predominantly related to leadership in the organization itself or the current state of the business/industry. It is not unusual to see signs of the Stockholm Syndrome in team members, which makes it extra hard to stop and clearly assess the situation. What I’ve found works here is to always focus on data and perform data‑driven crisis identification and decision‑making.

Finding leadership

We’ve already looked at a few different aspects and signs when identifying a crisis situation, but wouldn’t it be nice if, every time a crisis occurs, a leader steps up (sometimes unknown), while the rest of the team rallies behind, and it all just works out? While this situation may sound utopian, it is very much real. Once you scratch the surface, you may find a very fluid team or organization that has spent significant effort to get there.

The importance of taking action

None of the identifying factors would matter unless they’re actually involved in weighing or remedying a situation. Such involvement is all part of taking action, and this is a crucial aspect of what I believe to be the prime quality of leadership: taking decisive action while instilling trust.

Experience, confidence and trust

These three qualities are not the only ones that come up when we talk about leadership, but they are especially important in the context of mitigating crisis situations. How do you find such qualities in people so you can reach a crisis resolution with the least amount of damage? You build them.

Positive experiences build confidence; confidence fosters trust; trust enables decisive action. The cycle repeats, strengthening the organization’s ability to navigate future crises.

Confidence and Trust

Each situation is unique, but I’ve found that, regardless of whether a leader is well‑known to the team, emerges from within the organization, or is an external hire, positive experiences play a key role in establishing leadership qualities.

A crucial point is that the individual or the organization must create opportunities for people to try out leadership and discover where their qualities are most valued. Whether an experience feels positive or negative, it provides information about strengths and weaknesses, allowing teams to focus on what makes the most sense. This is where ownership and focus areas come into play.

Assigning Ownership

In multi‑crew aircraft, more than one pilot is capable of operating the aircraft, yet only one pilot controls the flight controls at any given time. This “two‑pilot problem” led to the Pilot Flying (PF) / Pilot Not Flying (PNF) concept, which clearly defines who is responsible for flying the aircraft.

What happens during a long‑haul flight when the PF wants a break?

According to the ALC‑36: Positive Aircraft Control — FAASafety.gov training course, the “Positive Exchange of Controls” procedure is performed:

- The flight instructor says to the student, “You have the flight controls.”

- The student acknowledges immediately: “I have the flight controls.”

- The instructor confirms again: “You have the flight controls.”

A visual check is also required to ensure the other person actually has the controls.

While this procedure may seem excessive in a software‑engineering setting, clear role assignment and ownership are equally essential. In many teams the roles are already defined, but crisis situations are often unprecedented. In such cases, roles and ownership may need to be revisited for the duration of the crisis. Failure to do so usually results in confusion, inaction, or—worse—role duplication that pulls the team in conflicting directions.

In general, every crisis is an opportunity to facilitate experiences, but the severity of the crisis and the organization’s risk tolerance must be taken into account.

Lead by Example

Here’s a plot twist (maybe not for all of you): leadership is more than just managing people. You don’t need to be a formal team lead to be a leader. Often, leadership is about inspiration and drive.

Consider a crisis in which a particular team is assigned to respond. The team leader can provide inspiration, coordination, and facilitation, but any team member selected at random also demonstrates leadership—whether they like it or not. The way that member handles their area and communicates with the rest of the team is, in fact, leadership, and it contributes to their experience and development.

Recovery

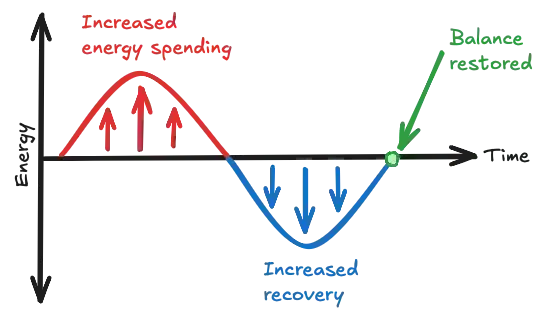

When we discuss leadership in crisis situations, recovery is inevitable. The more energy an individual or team expends during a crisis, the more time they need to recover and replenish.

What goes up must come down.

Spending time on recovery is arguably the most frequently disregarded—and most crucial—aspect of leadership. In physical training, recovery is what actually shapes and strengthens muscles and tissues, preparing them for future performance. In engineering, recovery periods boost morale and trust, not only in leadership but also within the team itself.

Retrospective

A retrospective (also called a post‑mortem) is a review of an incident from occurrence to resolution. It must be conducted in a safe space with a blameless attitude.

Key points

- Involve everyone who participated in the incident, and, when appropriate, relevant stakeholders.

- Aim to improve readiness and preparedness for future crises.

- Strengthen team dynamics and inter‑team communication.

Celebration

Celebrating after averting a crisis is vital for several reasons:

- It acknowledges the hard work, resilience, and teamwork that overcame the challenge.

- It boosts morale and reinforces a sense of community.

- It fosters a positive culture, encouraging continued engagement and motivation.

- It reminds everyone of their capabilities and the importance of their contributions.

By intentionally creating experiences, assigning clear ownership, leading by example, allowing time for recovery, reflecting in retrospectives, and celebrating successes, teams can build confidence, trust, and lasting leadership qualities.

Celebrating Success

Taking the time to celebrate reinforces a proactive mindset and strengthens the bonds within a team, paving the way to continued success and growth.

The Next Crisis

Part of the recovery is related to preparing for the next crisis. Depending on how likely it is, and how resilient the systems need to be, Chaos Engineering and other techniques can be introduced. However, a few things need to be kept in mind when preparing for—or even experiencing—the next crisis.

The Dangers of the Savior Complex

I relate this to the Savior Complex syndrome in psychology. In a software‑engineering setting, individuals or teams are often “voluntold” because it’s easier and “it worked last time.” Repeatedly putting such pressure on one person or team creates a single point of failure.

- What if the next crisis occurs while that person is on vacation or sick leave?

- The Savior Complex can erode the “safe space” – others may fear stepping up because of possible failure, or become passive, thinking “we already have a savior.”

Future crises are perfect opportunities to give other individuals or teams experience, while still considering the severity of the incident and the organization’s risk tolerance.

Prolonged Times of Crisis

When we compare physical activity—say, a marathon (endurance) versus a 100 m sprint (explosive)—the body’s biochemistry and energy utilization differ dramatically. You can have high output for a short period or low output for a long period, but not both.

The same applies to crisis situations. If a crisis drags on (turning a sprint into a marathon) or occurs too frequently, teams can become “injured.” In software engineering, these injuries manifest as:

- Silent quitting

- Burnout

- High turnover

How to Prevent Injuries

-

Introduce Frequent Recoveries

Break the overarching crisis into short milestones, each followed by a brief recovery and recognition period.

If the business can’t afford this, consider the next option. -

Implement Individual or Team Swapping

Treat the crisis like a relay race—pass the baton to the next individual or team.

For example, an on‑call rotation can keep the team prepared, focused, and motivated.

Bottom Line

Each organization and team is different. The most effective way to assess and address a crisis situation is honest communication.