Deep Dive into SQLite Storage

Source: Dev.to

Hello, I’m Maneshwar. I’m working on FreeDevTools online – a free, open‑source hub that gathers all dev tools, cheat codes, and TL;DRs in one place so developers don’t have to hunt across the web.

Yesterday we examined Page 1, the immutable starting point of every SQLite database file.

Today we move deeper into the parts of the file that are invisible at the SQL layer but are essential for SQLite’s space management, crash recovery, and long‑term performance.

This post continues the journey by explaining freelists, leaf pages, trunk pages, and finally journals – SQLite’s safety net.

Why SQLite Needs a Freelist

- SQLite never returns unused pages to the operating system immediately.

- Once a page is allocated, it stays in the file until an explicit shrink operation occurs.

- When rows are deleted, indexes dropped, or tables removed, those pages become inactive.

Instead of discarding them, SQLite places the inactive pages into a structure called the freelist – an internal inventory of unused pages that can be reused for future inserts without growing the file.

What Is the Freelist?

The freelist is a linked structure embedded directly inside the database file.

Key facts

| Offset | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 32 | First freelist trunk‑page number (stored in the file header) |

| 36 | Total count of free pages |

All free pages are tracked; there is no garbage collection or ambiguity. SQLite organizes the freelist as a rooted‑tree‑like list, starting from the file header and branching outward.

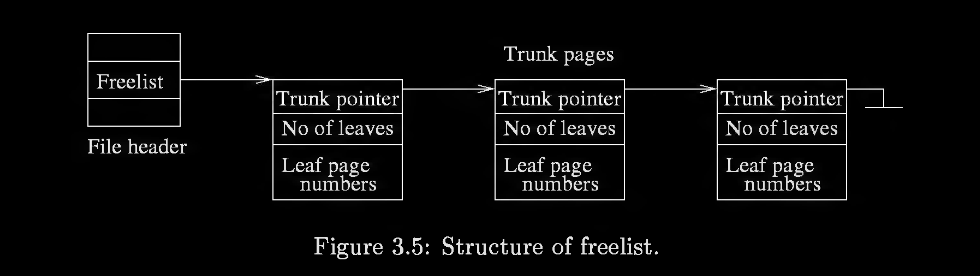

Trunk Pages and Leaf Pages (Freelist Pages)

Freelist pages come in two sub‑types.

Trunk Pages

A trunk page acts as a directory of free pages. Its layout (starting at the beginning of the page) is:

| Bytes | Content |

|---|---|

| 4 | Page number of the next trunk page (or 0 if none) |

| 4 | Number of leaf pointers stored on this trunk |

| N × 4 | Page numbers of leaf pages |

Each trunk page can reference many free pages at once.

Leaf Pages

A leaf page is a free page that contains no meaningful structure. Its content is unspecified and may contain leftover data from previous use. Leaf pages are the actual reusable pages; trunk pages merely point to them.

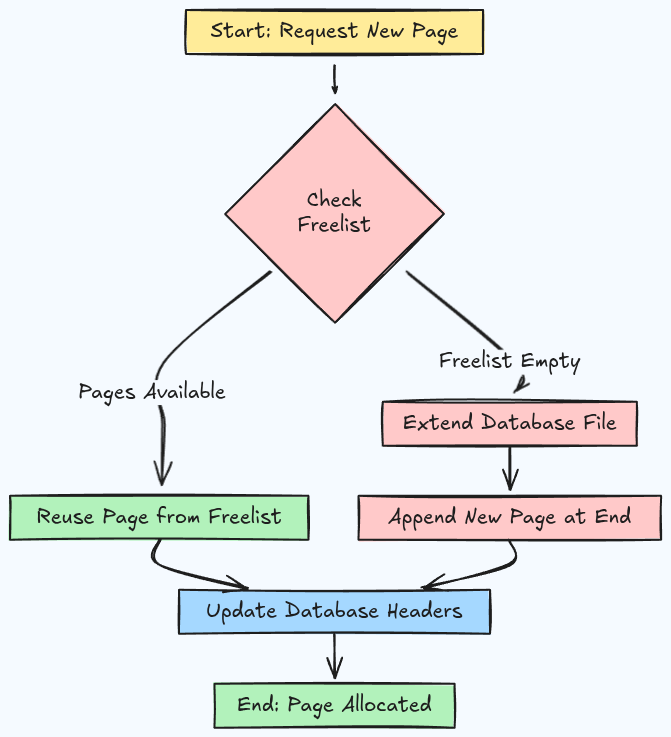

How Pages Enter and Leave the Freelist

- When a page becomes inactive, SQLite adds it to the freelist. The page remains physically inside the file.

- When new data must be written, SQLite pulls pages from the freelist.

This explains why SQLite databases often grow but don’t shrink automatically.

Shrinking the Database: VACUUM and Autovacuum

If the freelist grows too large, disk usage becomes wasteful. SQLite provides two solutions.

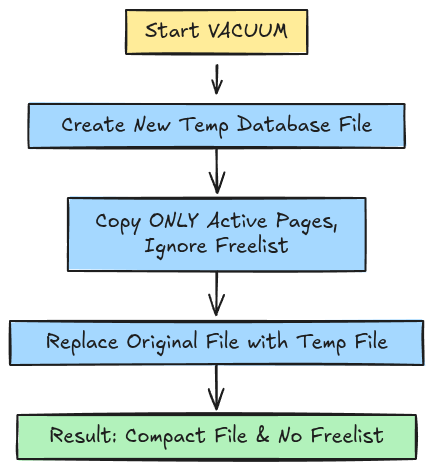

VACUUM

VACUUM is a heavyweight but precise operation that rebuilds the entire database file, discarding unused pages.

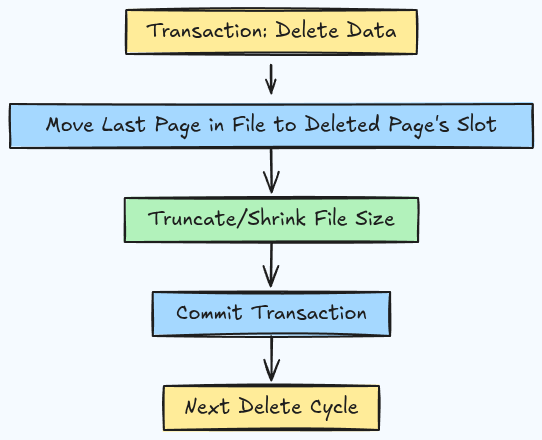

Autovacuum Mode

Autovacuum trades a small runtime overhead for continuous space hygiene, automatically moving free pages to the end of the file as they become available.

Journal Files in SQLite

A journal is a crash‑recovery file that records database changes so SQLite can roll back incomplete transactions. It guarantees atomicity and durability, ensuring the database is never left half‑written after a failure.

SQLite historically uses legacy journaling, which includes:

- Rollback journal

- Statement journal

- Master journal

From SQLite 3.7.0 onward, a database uses either legacy journaling or WAL, never both at the same time. In‑memory databases skip journaling entirely (the journal lives only in memory).

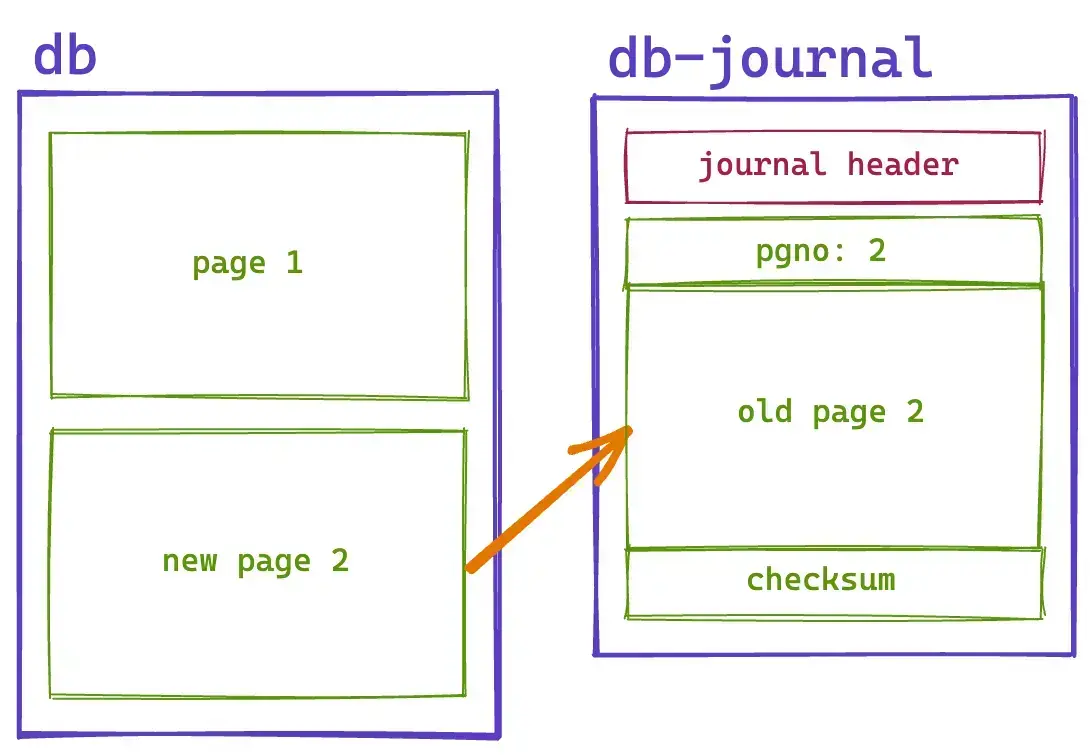

Rollback Journal: SQLite’s Safety Harness

Each database has one rollback‑journal file:

- Stored in the same directory as the database.

- Named by appending

-journalto the database file name. - Created at the start of a write transaction.

- Deleted (by default) when the transaction finishes.

Rollback journals store before‑images of database pages, allowing SQLite to restore the database if something goes wrong.

Rollback Journal Structure

(The original content stopped here; you can continue describing the on‑disk layout of the rollback journal if needed.)

Write‑Ahead Log (WAL) Journal Overview

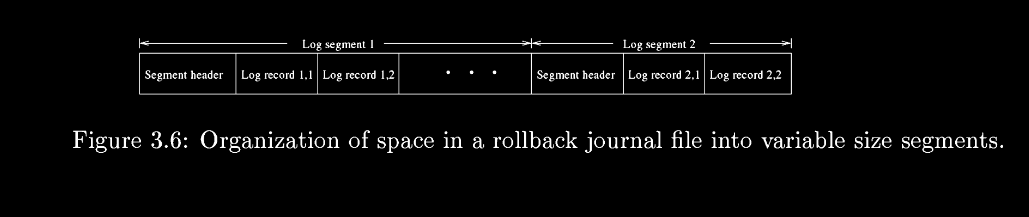

The SQLite journal is divided into log segments.

Each segment consists of:

- Segment header

- One or more log records

Most of the time there is only one segment; multiple segments appear only in special situations.

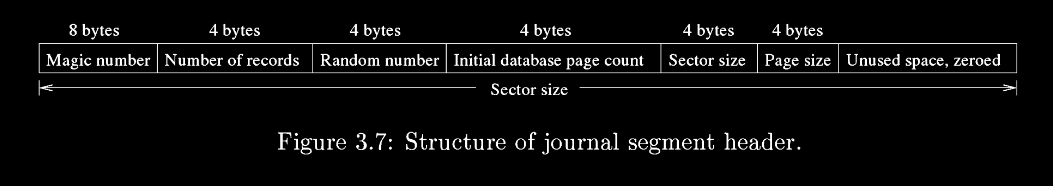

Segment Header – The First Line of Defense

Each segment header starts with eight magic bytes:

D9 D5 05 F9 20 A1 63 D7These bytes exist solely for sanity checks.

The header also stores:

- Number of log records (

nRec) - Random value for checksum calculations

- Original DB page count

- Disk sector size

- DB page size

The header always occupies exactly one disk sector, and all values are stored in big‑endian format.

Journal Retention Modes

By default, SQLite deletes the journal file after a commit or rollback. You can change this behavior with the following modes:

| Mode | Description |

|---|---|

DELETE | Default – removes the journal file after each transaction. |

PERSIST | Keeps the journal file but invalidates its header between uses. |

TRUNCATE | Truncates the journal file to zero length after each transaction. |

In exclusive locking mode, the journal file persists across transactions, but its header is either invalidated or truncated between uses.

Asynchronous Transactions (Unsafe but Fast)

SQLite supports an asynchronous mode that sacrifices durability for speed:

- Journal and DB files are never flushed to disk.

- Transactions complete much faster.

nRecis set to ‑1.- Recovery relies on the file size rather than metadata.

Warning: This mode is not crash‑safe and should be used only for development or testing, where performance gains outweigh the risk of data loss.

Why This Layer Matters

At this low level SQLite reveals its core philosophy:

- Space is recycled, not discarded.

- Safety is achieved with precise, minimal metadata.

- Nothing is implicit; everything is explicitly tracked.

- Recovery logic is encoded directly into the file structure.

My experiments and hands‑on examples related to SQLite can be found here:

lovestaco/sqlite – SQLite examples

References

- SQLite Database System: Design and Implementation – Sibsankar Haldar (n.d.)

👉 Check out: FreeDevTools

Any feedback or contributions are welcome! The project is online, open‑source, and ready for anyone to use.

⭐ Star it on GitHub: HexmosTech/FreeDevTools