Beyond FFI: Zero-Copy IPC with Rust and Lock-Free Ring-Buffers

Source: Dev.to

By: Rafael Calderon Robles | LinkedIn

1. The Call‑Cost Myth: Marshalling and Runtimes

It’s a common misconception that the overhead is just the CALL instruction. In a modern environment (e.g., Python/Node.js → Rust) the real “tax” is paid at three distinct checkpoints:

| Checkpoint | What Happens |

|---|---|

Marshalling / Serialization (O(n)) | Converting a JS object or Python dict into a C‑compatible structure (contiguous memory). This burns CPU cycles and pollutes the L1 cache before Rust even touches a byte. |

| Runtime Overhead | Python must release and reacquire the GIL; Node.js crossing the V8/Libuv barrier incurs expensive context switches. |

| Cache Thrashing | Jumping between a GC‑managed heap and the Rust stack destroys data locality. |

If you’re processing 100 k messages/second, the CPU spends more time copying bytes across borders than executing business logic.

2. The Solution: SPSC Architecture over Shared Memory

The alternative is a lock‑free ring buffer residing in a shared‑memory segment (mmap). We establish an SPSC (single‑producer single‑consumer) protocol where the host writes and Rust reads, with zero syscalls or mutexes in the hot path.

Anatomy of a Cache‑Aligned Ring Buffer

To run this in production without invoking undefined behavior (UB) we must be strict about memory layout.

use std::sync::atomic::{AtomicUsize, Ordering};

use std::cell::UnsafeCell;

// Design constants

const BUFFER_SIZE: usize = 1024;

// 128 bytes to cover both x86 (64 bytes) and Apple Silicon (128 bytes pair‑prefetch)

const CACHE_LINE: usize = 128;

// GOLDEN RULE: Msg must be POD (Plain Old Data).

// Forbidden: String, Vec, or raw pointers. Only fixed arrays and primitives.

#[repr(C)]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)] // Guarantees bitwise copy

pub struct Msg {

pub id: u64,

pub price: f64,

pub quantity: u32,

pub symbol: [u8; 8], // Fixed‑size byte array for symbols

}

#[repr(C)]

pub struct SharedRingBuffer {

// Producer isolation (Host)

// Initial padding to avoid adjacent hardware prefetching

_pad0: [u8; CACHE_LINE],

pub head: AtomicUsize, // Write: Host, Read: Rust

// Consumer isolation (Rust)

// This padding is CRITICAL to prevent false sharing

_pad1: [u8; CACHE_LINE - std::mem::size_of::()],

pub tail: AtomicUsize, // Write: Rust, Read: Host

_pad2: [u8; CACHE_LINE - std::mem::size_of::()],

// Data: Wrapped in UnsafeCell because Rust cannot guarantee

// the Host isn’t writing here (even if the protocol prevents it).

pub data: [UnsafeCell; BUFFER_SIZE],

}

// Note: In production, use #[repr(align(128))] instead of manual arrays

// for better portability, but manual padding illustrates the concept here.

3. The Protocol: Acquire/Release Semantics

Forget mutexes—use memory barriers.

-

Producer (Host):

- Write the message to

data[head % BUFFER_SIZE]. - Increment

headwith Release semantics.

This guarantees the data write is visible before the index update is observed.

- Write the message to

-

Consumer (Rust):

- Read

headwith Acquire semantics. - If

head != tail, read the data and then incrementtail.

- Read

The synchronization is hardware‑native; no operating‑system intervention is required.

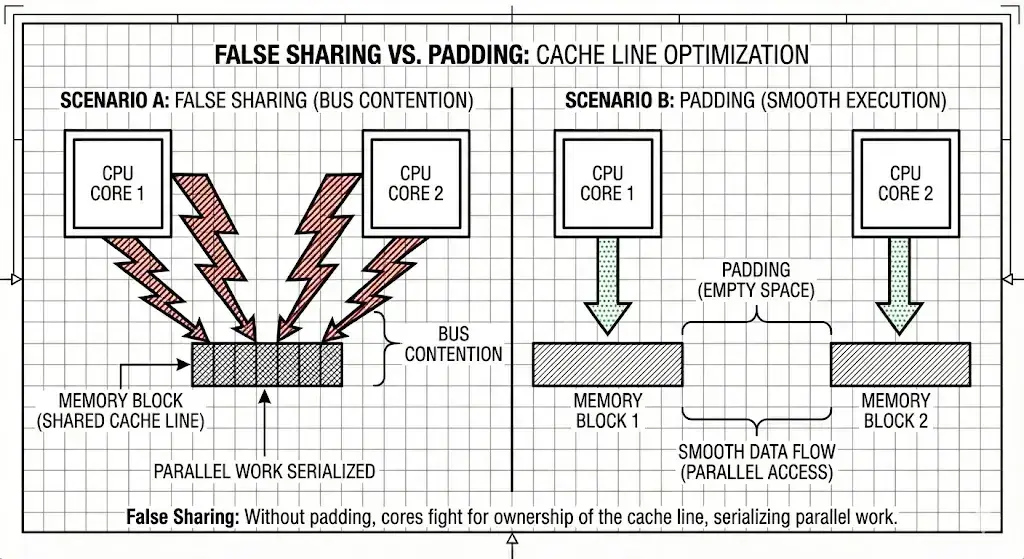

4. Mechanical Sympathy and False Sharing

Throughput collapses if we ignore the hardware. False sharing occurs when head and tail reside on the same cache line.

Core 1 (e.g., Python) updates head → the entire cache line is invalidated.

Core 2 (Rust) then reads tail (on that same line) → it must stall until the cache line is synchronized via the MESI protocol. This can degrade performance by an order of magnitude.

Solution: Force a physical separation of at least 128 bytes (padding) between the two atomics, as shown in the struct above.

5. Wait Strategy: Don’t Burn the Server

An infinite loop (while true) will consume 100 % of a core, which is unacceptable in cloud environments or battery‑powered devices.

The correct strategy is Hybrid:

- Busy Spin (≈ 50 µs): Call

std::thread::yield_now(). Yield execution to the OS but stay “warm.” - Park/Wait (Idle): If no data arrives after X attempts, use a lightweight blocking primitive (e.g.,

Futexon Linux or aCondvar) to sleep the thread until a signal is received.

// Simplified Hybrid Consumption Example

loop {

let current_head = ring.head.load(Ordering::Acquire);

let current_tail = ring.tail.load(Ordering::Relaxed);

if current_head != current_tail {

// 1. Calculate offset and access memory (unsafe required due to FFI nature)

let idx = current_tail % BUFFER_SIZE;

let msg_ptr = ring.data[idx].get();

// Volatile read prevents the compiler from caching the value in registers

let msg = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(msg_ptr) };

process(msg);

ring.tail.store(current_tail + 1, Ordering::Release);

} else {

// Backoff / Hybrid Wait strategy

spin_wait.spin();

}

}6. The Pointer Trap: True Zero‑Copy

“Zero‑Copy” in this context comes with fine print.

Warning: Never pass a pointer (

Box,&str,Vec) inside theMsgstruct.

The Rust process and the host process (Python/Node) have different virtual address spaces. A pointer such as 0x7ffee… that is valid in Node is garbage (and a likely segfault) in Rust.

You must flatten your data. If you need to send variable‑length text, use a fixed buffer ([u8; 256]) or implement a secondary ring‑buffer dedicated to a string‑slab allocator, but keep the main structure flat (POD).

Conclusion

Implementing a shared‑memory ring‑buffer transforms Rust from a “fast library” into an asynchronous co‑processor. We eliminate marshalling costs and achieve throughput limited almost exclusively by RAM bandwidth.

However, this increases complexity: you manage memory manually, you must align structures to cache lines, and you must protect against race conditions without the compiler’s help. Use this architecture only when standard FFI is demonstrably the bottleneck.

Tags: #rust #performance #ipc #lock‑free #systems‑programming

Further Reading